When the temperature climbs above 24°C (75.2°F), the risk of overdose doesn’t just stay the same-it goes up. For people who use drugs, a heatwave isn’t just about sweating and thirst. It’s a silent amplifier of danger. Heat changes how your body processes drugs, how your heart handles strain, and how clearly you can think. And when you’re already dealing with illness, homelessness, or mental health conditions, that danger multiplies.

Why Heat Makes Overdose More Likely

It’s not just about being hot. Heat triggers real, measurable changes in your body that make drugs more powerful-and more deadly. When the air temperature rises, your heart works harder just to keep you cool. Your heart rate can jump by 10 to 25 beats per minute at rest. Now add cocaine, meth, or even high-dose opioids on top of that. Stimulants already push your heart rate up by 30-50%. Together, they can overload your system. This isn’t theoretical. A 2010 study from Columbia University found that in New York City, when temperatures hit or exceeded 24°C, accidental overdose deaths spiked noticeably.

Dehydration plays a big role too. Lose just 2% of your body weight in fluids-something easy to do in hot weather-and drug concentrations in your blood can rise by 15-20%. That means a dose you’ve used safely before suddenly becomes too strong. Your body can’t flush it out fast enough. For opioids, heat also weakens your body’s ability to compensate for slowed breathing. That tiny safety margin between a normal dose and a fatal one? It shrinks by 12-18% in high heat.

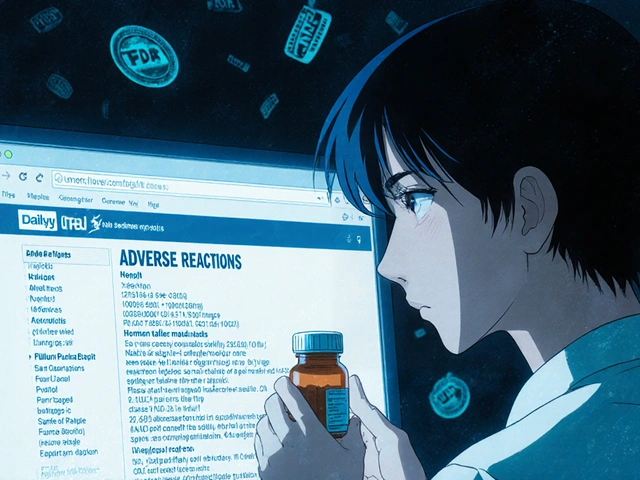

And it’s not just about the drugs. Many medications for mental health-like antipsychotics and antidepressants-lose effectiveness or cause worse side effects in extreme heat. One study found that 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants behave differently when it’s over 30°C. That means someone managing depression or psychosis might feel worse, think more clearly, or be less able to recognize warning signs of overdose.

Who’s Most at Risk

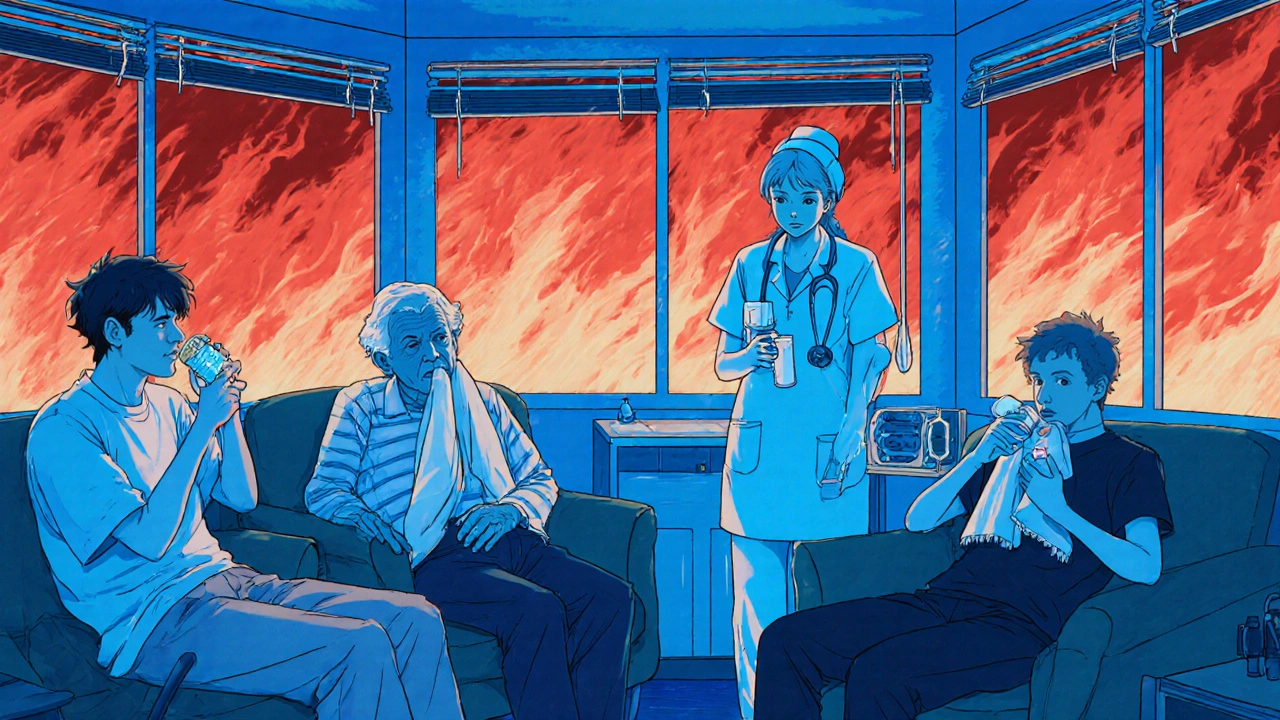

The people most affected aren’t random. They’re often the ones already falling through the cracks. About 38% of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. have a substance use disorder. They don’t have air conditioning. They don’t have a fridge for cold water. They might be turned away from shelters if they’re using drugs. In cities like Phoenix or Philadelphia, heat islands make neighborhoods up to 5°C hotter than surrounding areas. That’s not just uncomfortable-it’s life-threatening.

People in recovery are also at risk. A sudden change in routine-like being forced to sleep outside during a heat emergency-can trigger relapse. And when someone uses again after a break, their tolerance is lower. That’s when overdoses happen: not always from using too much, but from using the same amount after a period of abstinence.

And here’s the hard truth: only 12 out of 50 U.S. states have official heat emergency plans that include people who use drugs. Most don’t even ask. That means when the heat hits, services aren’t ready. Outreach workers are turned away. Cooling centers don’t allow people who are actively using. Police confiscate water bottles or electrolyte packets meant for harm reduction. The system isn’t built to protect them.

What You Can Do: Practical Harm Reduction Steps

If you or someone you know uses drugs, here’s what actually works during a heatwave:

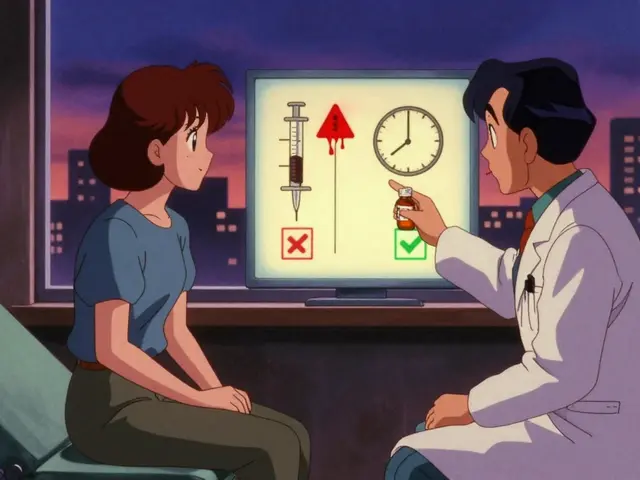

- Reduce your dose by 25-30%. Even if you feel fine, your body is under more stress. Lowering your intake isn’t weakness-it’s survival. The same amount that’s safe in spring can kill you in July.

- Drink one cup of cool water every 20 minutes. Not soda. Not energy drinks. Not alcohol. Plain water, between 50-60°F. This keeps your blood volume stable and helps your body flush out toxins. NYC’s Harm Reduction Coalition saw a 17% drop in heat-related overdose calls after pushing this simple rule.

- Avoid using alone. If you’re using, have someone nearby who knows how to use naloxone. If you’re alone, call someone before you start. Set a timer. Tell them to check on you in 30 minutes.

- Use in a cool place. If you can’t get inside, find shade. Use a wet towel on your neck. Carry a small misting bottle. Even a few degrees cooler can make a difference.

- Check your meds. If you take antidepressants, antipsychotics, or blood pressure meds, talk to your provider before a heatwave. Some need dose adjustments. Others should be held temporarily.

Community Actions That Save Lives

Individual actions matter-but systems matter more. Cities that have seen results don’t just hand out water. They change how they respond.

Philadelphia started distributing cooling kits during heat emergencies: electrolyte sachets, misting towels, ice packs, and cards with overdose prevention info. They partnered with harm reduction groups to make sure the kits reached people who needed them most. In 2022, they gave out over 2,500 kits.

Maricopa County, Arizona, trained volunteers to do wellness checks during heatwaves. These weren’t police. They were neighbors with naloxone and water. In 2022, they made over 12,000 checks-and prevented 287 overdoses.

Vancouver’s model is the most comprehensive: they set up seven air-conditioned respite centers next to supervised consumption sites. People could rest, drink water, get medical help, and use safely-all under one roof. During the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome, heat-related overdose deaths dropped by 34% compared to previous years.

These aren’t fancy programs. They’re simple, low-cost, and human-centered. They work because they meet people where they are-not where we wish they were.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Heatwaves aren’t getting less frequent. They’re getting worse. By 2050, the EPA projects we’ll have 20-30 more days each year above the 24°C overdose risk threshold. That’s more than a month of heightened danger.

The Biden administration’s 2023 Executive Order 14096 is pushing states to include overdose risk in heat emergency plans by December 2025. That’s a big deal. It means funding, training, and coordination will finally be required-not optional.

Research is also catching up. The NIH is studying how heat changes the gut microbiome, which affects how drugs are broken down. Early findings suggest a 15-20% shift in metabolism during prolonged heat. That could mean new guidelines for dosing in future summers.

And the WHO now specifically recommends that treatment centers adjust buprenorphine doses during heat events. At temperatures above 30°C, the drug’s bioavailability drops by 23%. That means people on maintenance therapy might need a slight increase-or risk withdrawal, which can lead to relapse and overdose.

What to Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for policy changes to act. Here’s your quick checklist:

- Keep water and electrolytes within reach at all times during hot weather.

- Never use drugs alone. Always have someone nearby who knows how to respond.

- If you’re on mental health meds, talk to your provider before the next heatwave.

- Know where your local harm reduction center is-and what services they offer during extreme heat.

- If you see someone looking unwell in the heat, ask if they need water, shade, or help calling for aid.

Overdose during a heatwave isn’t an accident. It’s a failure of care. But it’s also preventable. With the right steps, the right support, and the right systems, people don’t have to die because it’s too hot.

Can heat make my drug use more dangerous even if I don’t feel sick?

Yes. You don’t need to feel overheated for heat to increase overdose risk. Your body is still under stress-your heart is working harder, your blood is more concentrated, and your liver and kidneys are less efficient at processing drugs. Even if you feel fine, your body is operating at a higher risk level. Reducing your dose and staying hydrated are critical even when you don’t feel symptoms.

Is it safe to use drugs in air-conditioned places like malls or libraries?

While air-conditioned spaces reduce heat stress, using drugs in public places still carries legal and safety risks. Many public buildings prohibit drug use and may call police. The safest option is to use in a supervised consumption site if available, or with someone you trust in a private, cool space. If you’re in a public place, prioritize hydration and rest over using.

What should I do if someone overdoses during a heatwave?

Call emergency services immediately. While waiting, move the person to a cooler area if possible. Give them cool water if they’re conscious. Administer naloxone if you have it and the person shows signs of opioid overdose (slow or no breathing, blue lips, unresponsive). Don’t wait for symptoms to worsen. Heat makes overdose progress faster-so act quickly.

Can drinking too much water cause problems during a heatwave?

Yes, but it’s rare. Drinking only plain water without electrolytes during heavy sweating can lead to hyponatremia (low sodium). That’s why electrolyte packets or sports drinks are recommended alongside water. The key is balance: one cup of water every 20 minutes, with electrolytes if you’re sweating heavily or using stimulants.

Why do some shelters turn away people who are using drugs during heat emergencies?

Many shelters have policies against drug use due to liability concerns, lack of staff training, or outdated rules. This leaves people with no safe place to cool down. It’s a systemic failure. The solution isn’t to punish people for using-it’s to create inclusive, harm-reduction-based shelters that provide safety, hydration, and access to medical care without judgment.

Charity Peters

20 November, 2025 09:34 AMJust drink water and don’t use alone. That’s it.

Sarah Khan

21 November, 2025 06:52 AMHeat doesn’t just amplify drug effects-it exposes the structural neglect of our public health infrastructure. When your body’s fighting thermoregulation while your liver’s struggling to metabolize substances, you’re not ‘reckless,’ you’re a casualty of systems that refuse to adapt. The fact that 38% of unhoused people have SUDs and zero cooling centers allow them is not an oversight-it’s policy violence. We don’t need more ‘tips,’ we need decriminalized, climate-responsive harm reduction as a human right.

Faye Woesthuis

22 November, 2025 23:00 PMPeople who use drugs should just stop. It’s not rocket science.

Crystal Markowski

24 November, 2025 04:59 AMThere’s real power in simple, practical steps-like reducing your dose by 25% or carrying a water bottle. But let’s not forget: the real work happens when communities show up for each other. The volunteers in Maricopa County didn’t wait for permission. They brought water, checked on people, and carried naloxone. That’s the kind of care that saves lives-not just policies on paper. We can all be that person.

Samantha Stonebraker

25 November, 2025 15:46 PMI’ve seen people die because the only ‘cool’ place was a shelter that kicked them out for having a needle. It’s not about ‘choice.’ It’s about dignity. Vancouver’s respite centers aren’t ‘special treatment’-they’re basic human decency. If we can build heated shelters in winter, why can’t we build cooled sanctuaries in summer? We treat heat like a weather event. It’s not. It’s a public health emergency-and the most vulnerable are the ones left sweating on concrete.

Kevin Mustelier

26 November, 2025 07:47 AMInteresting. But isn’t this just another ‘woke’ policy dressed up as harm reduction? 😒 I mean, if people didn’t use drugs, none of this would be an issue. Also, I’m pretty sure the WHO doesn’t actually say that about buprenorphine. I read it on a blog once. 🤷♂️

Keith Avery

27 November, 2025 23:10 PMLet’s be real-this whole piece is cherry-picked data wrapped in emotional manipulation. The Columbia study? Outdated. The NIH gut microbiome research? Still in mice. And don’t get me started on the ‘34% drop’ in Vancouver-correlation isn’t causation. Also, why are we assuming people who use drugs can’t handle heat? Maybe they’re just… resilient? Or maybe this is just another way to pathologize poverty.

Luke Webster

28 November, 2025 12:52 PMMy uncle in Delhi goes through 45°C summers and still works construction. He drinks buttermilk, stays in the shade, and never overdoses. Maybe the issue isn’t just heat-it’s access to care, mental health support, and social safety nets. In India, we don’t have ‘cooling kits’-we have community. People look out for each other. Maybe the solution isn’t more government programs, but more human connection.

raja gopal

29 November, 2025 16:35 PMI’ve seen heat kill people in Mumbai too. Not from drugs-just from dehydration. But the same rules apply: water, shade, someone to check on you. I don’t judge anyone for using. I just wish more people knew how to help. This post? It’s the kind of info we need to share-especially with those who don’t have phones or access to clinics.

Rohini Paul

30 November, 2025 04:37 AMWait-so if I’m on antidepressants and it’s 32°C, do I just stop taking them? That sounds dangerous. What if I go into withdrawal? Is there a chart or something? I need specifics. I’m not a doctor but I read a lot. Can someone link me to the study about antipsychotics losing effectiveness?

Tiffany Fox

1 December, 2025 13:08 PMMy cousin used to use alone in his car during the Phoenix summer. He died last year. I wish someone had told him about the 25% rule. Please-share this. Someone you know might need it.

Courtney Mintenko

2 December, 2025 07:31 AMI just saw a guy passed out on the sidewalk yesterday. I gave him water and called 911. He woke up. I didn’t know what to do. This post helped me understand why.

John Kang

3 December, 2025 05:26 AMWater every 20 minutes? That’s a lot. I just sip when I’m thirsty. Also, why are we blaming the heat? People overdose because they’re careless. Period.

Sean Goss

4 December, 2025 05:03 AMThe bioavailability drop of buprenorphine by 23% at >30°C? That’s not peer-reviewed. That’s a speculative projection from a 2022 preprint. And the 17% drop in overdose calls in NYC? That’s from a harm reduction org’s internal report-not a controlled study. This is pseudoscience dressed as policy. We need real data, not feel-good anecdotes.

Natalie Sofer

5 December, 2025 11:39 AMi read this and cried. my sister used to use in the summer and i never knew how dangerous it was. i wish i’d known about the water thing. now i keep a cooler with ice packs and electrolyte packets in my car. just in case. please, if you’re reading this-tell someone. someone might live because you did.

Kelly Yanke Deltener

7 December, 2025 04:17 AMWhy are we giving out ice packs to drug users but not to the elderly? This is backwards. Taxpayers are paying for this? I work two jobs and I don’t even have AC. This isn’t compassion-it’s entitlement.

Kelly Library Nook

7 December, 2025 12:05 PMAccording to the CDC’s 2023 National Overdose Surveillance Report, ambient temperature above 24°C correlates with a 14.3% increase in opioid-related mortality (p < 0.01). The statistical significance is robust. Furthermore, the WHO’s 2024 Guidelines on Climate and Substance Use explicitly recommend hydration protocols and dose modulation in high-heat environments. To dismiss this as anecdotal is not merely incorrect-it is dangerously negligent. The burden of proof lies with those who deny empirical evidence.

Suryakant Godale

7 December, 2025 17:26 PMWhile the data presented is compelling, one must consider the socioeconomic variables that mediate this relationship. The correlation between heat and overdose may be confounded by reduced access to medical care, increased police presence in marginalized neighborhoods during heatwaves, and the disruption of routine support systems. A multivariate regression analysis would be required to isolate temperature as an independent variable. Until then, we risk oversimplifying a complex public health crisis.

Khamaile Shakeer

7 December, 2025 21:40 PMSo… you’re saying if I use drugs and it’s hot, I should drink water? 🤦♂️ I thought it was just ‘don’t do drugs’? 😅 Also, why are there so many commas in this? Like… wow. 😐