When you pick up a bottle of pills, you might see two names: one you recognize from ads, and another that looks like a jumble of letters and numbers. That second name isn’t random-it’s the generic name, and it follows strict rules designed to keep you safe. These rules are set by two major systems: the United States Adopted Names (USAN) a nonproprietary naming system for drugs in the United States, established in 1964 and managed by the USAN Council and the International Nonproprietary Names (INN) a global naming system managed by the World Health Organization since 1950 to ensure consistent drug identification worldwide. Understanding how these work helps explain why some drugs have different names in different countries-and why that matters for your health.

Why Do Drugs Have Two Names?

Every drug has a brand name and a generic name. The brand name is what companies use to market the drug-think Advil, Lipitor, or Zoloft. It’s catchy, trademarked, and owned by one company. The generic name, on the other hand, is the official scientific label. It’s not owned by anyone. It’s public. It’s used by doctors, pharmacists, regulators, and researchers everywhere.

Why does this matter? Because if every drug had its own unique name with no system behind it, mistakes would happen. Imagine a doctor writing “Lipitor” instead of “atorvastatin” and a pharmacist in another country not recognizing it. Or worse-two drugs with similar-sounding names getting mixed up. That’s why USAN and INN exist: to make sure every active ingredient has one clear, unambiguous name.

How USAN and INN Work

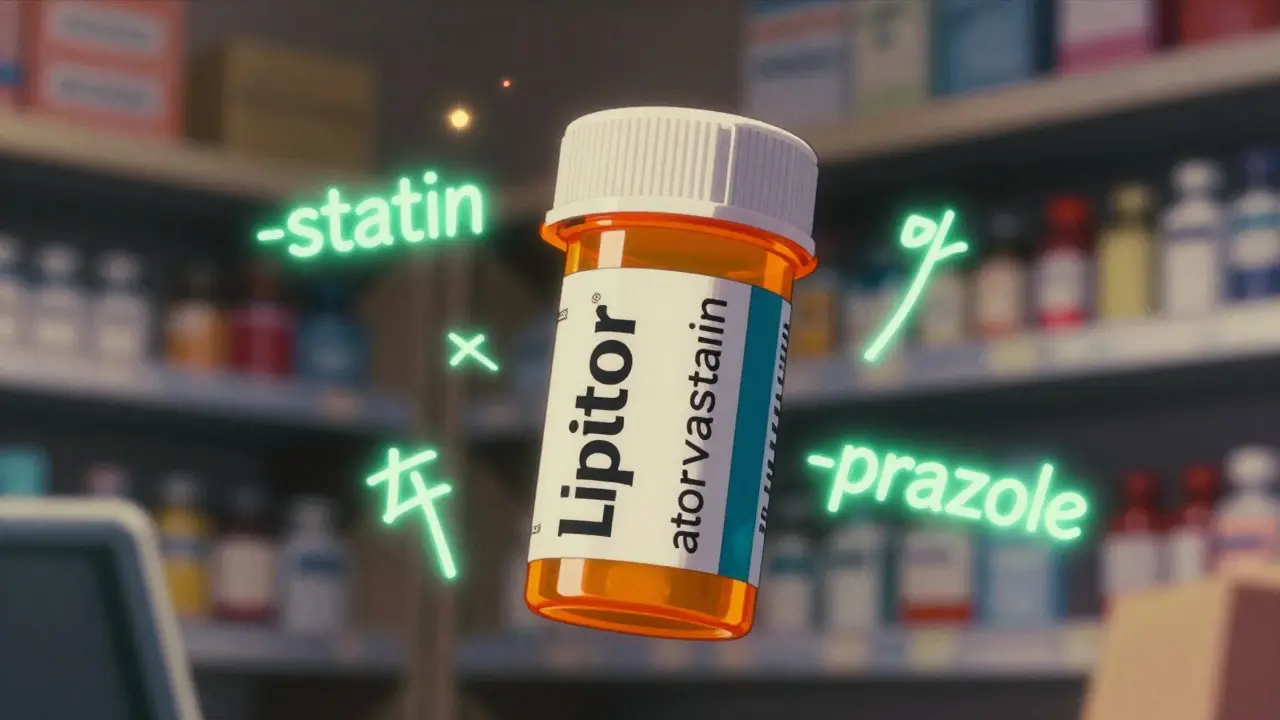

Both USAN and INN use a system built around “stems.” A stem is the ending part of a drug name that tells you what kind of drug it is. For example:

- -prazole = proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole)

- -statin = cholesterol-lowering drugs (like atorvastatin)

- -mab = monoclonal antibodies (like adalimumab)

- -virdine = HIV antivirals (like zidovudine)

The beginning of the name-the part before the stem-is usually made up. It doesn’t mean anything. It’s just there to make the name unique. For example, “omeprazole” has “ome-” as a made-up prefix and “-prazole” as the stem. The same logic applies to “eser-” in esomeprazole, which signals it’s a specific version (stereoisomer) of omeprazole.

Drug companies don’t just pick names on their own. They submit up to six options to both USAN and INN. Then, experts check them for conflicts-do they sound too similar to another drug? Are they already trademarked? Do they fit the stem rules? This process takes 18 to 24 months. About 30-40% of proposed names get rejected because they’re too close to existing ones.

USAN vs. INN: What’s the Difference?

Most of the time, USAN and INN names are the same. In fact, about 95% of drugs have matching names. But there are a few well-known exceptions:

- Acetaminophen (USAN) vs. Paracetamol (INN)

- Albuterol (USAN) vs. Salbutamol (INN)

- Rifampin (USAN) vs. Rifampicin (INN)

These differences exist because the USAN Council prioritizes historical usage in the U.S. medical system. For example, “acetaminophen” has been used in American hospitals since the 1950s, so it stuck-even though the rest of the world uses “paracetamol.”

INN, on the other hand, aims for global consistency. It doesn’t care about U.S. history. It cares about what works everywhere. That’s why INN names are used in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The FDA accepts USAN names for all drugs sold in the U.S., and the European Medicines Agency requires INN names for approval in Europe.

Why This System Keeps You Safe

Medication errors due to confusing drug names cost the U.S. healthcare system about $2.4 billion a year. That’s not just money-it’s lives. A study from the Institute of Medicine found that nearly half of all medication errors in hospitals involve name confusion.

Stems help prevent that. When a doctor sees “-mab,” they know it’s a monoclonal antibody. When they see “-prazole,” they know it’s for stomach acid. Even if they’ve never heard of the exact drug, they can guess its class and use. That’s crucial in emergencies.

For example, if a patient is given a new drug ending in “-virdine,” a pharmacist immediately knows it’s an HIV medication-even if it’s a brand-new compound. That speeds up treatment and reduces mistakes.

How New Drugs Are Named Today

The process starts early-usually during Phase 1 clinical trials. That’s when the drug company submits its name proposals. They work with naming consultants who run simulations: how does it sound? Is it too close to “Zoloft”? Could a nurse misread it as “Lipitor”? They test it across languages, cultures, and even handwriting styles.

It’s not unusual for a company to go through 15 to 20 name options before settling on one. And even then, it might get rejected. The USAN Council gets around 250 requests a year. Only about 60% get approved on the first try.

Once a name is approved by USAN, it goes to WHO’s INN team. They review it for global compatibility. If they find a problem-say, it sounds like a drug already used in Brazil-they’ll suggest a change. In rare cases, they’ll even propose a completely different name.

And here’s something surprising: about 65% of drugs that get a USAN name never even make it to market. They fail in trials. But their names stay on file-just in case another company wants to use them later.

What’s Changing in Drug Naming?

Traditional stems work great for pills and injections. But what about gene therapies? RNA drugs? Antibody-drug conjugates? These newer treatments don’t fit neatly into “-mab” or “-prazole.”

In 2021, WHO updated its rules for monoclonal antibodies to account for new types like bispecific antibodies and Fc-engineered versions. USAN followed suit. But experts agree: we’re running out of good stems.

Some scientists argue the system is outdated. For example, a drug might start as a treatment for arthritis but later be used for lupus. Should its name change? No-it stays the same. The stem reflects its original chemical action, not its current use.

Still, the system has held up. It’s adaptable, consistent, and-most importantly-it saves lives. As new therapies emerge, USAN and INN are working together to build new stems. But they won’t create them unless the science demands it. And they’ll only do it if there’s enough data to support it.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to memorize stems. But you should know this: if your doctor prescribes a drug by its generic name, you’re getting the same medicine as the brand version-just cheaper. And if you’re traveling overseas, your “albuterol” inhaler might be labeled “salbutamol.” That’s not a mistake. It’s the system working.

Always check the active ingredient on the label. If you see “acetaminophen” on your bottle but your home pharmacy sells “paracetamol,” don’t panic. They’re the same thing.

And if you’re ever confused about a drug name, ask your pharmacist. They’re trained to spot name confusion before it becomes a problem.

Looking Ahead

The push for global harmony is growing. More countries are adopting INN names even in regions that once used USAN-style names. The FDA and WHO are collaborating more than ever. But some differences will stay-like acetaminophen/paracetamol-because changing them now would cause more confusion than keeping them.

For now, the system works. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we have. And every time a doctor writes a prescription, a pharmacist fills it, or a patient takes a pill, this naming system is quietly making sure they all mean the same thing.

What’s the difference between a brand name and a generic name?

A brand name is the trademarked name given by a drug company for marketing (like Advil or Zoloft). A generic name is the official, nonproprietary name assigned by USAN or INN (like ibuprofen or sertraline). Generic names are used by all manufacturers once the patent expires and are always in the public domain.

Why do some drugs have different names in the U.S. and other countries?

This happens because the U.S. uses USAN names, while most other countries use INN names. While 95% of names match, a few historical differences remain-like acetaminophen (U.S.) vs. paracetamol (global). These differences reflect long-standing medical usage in each region.

How are drug names chosen?

Drug companies propose up to six names during early clinical trials. Experts from USAN and WHO review them for clarity, uniqueness, and adherence to naming stems. Names are checked against existing drugs, trademarks, and language risks. The process takes 18-24 months, and about 40% of proposed names are rejected.

Do generic names ever change?

No. Once a drug gets its generic name, it stays the same-even if its uses change. For example, drugs ending in “-prazole” were originally for ulcers, but now treat GERD and other conditions. The name doesn’t change because the chemical structure and stem remain the same.

Are generic drugs less effective than brand-name drugs?

No. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredient, dosage, and strength as brand-name versions. They’re required by law to work the same way. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, packaging, or cost.

What happens if a drug name causes confusion?

If a name is found to be too similar to another drug, regulators can reject it before approval. In rare cases, if a drug is already on the market and causes confusion, the FDA or WHO may issue safety alerts or recommend changes in labeling. But renaming a drug after approval is extremely rare.

Daniel Dover

14 February, 2026 15:44 PMStems are genius. Saw a drug ending in -virdine last week and instantly knew it was an antiviral. No guesswork. Saves time. Saves lives.

Simple. Effective.

Kaye Alcaraz

16 February, 2026 05:21 AMThis system is one of the quiet heroes of modern medicine. No flashy ads. No viral videos. Just clarity. Every pharmacist, nurse, and doctor benefits from this invisible architecture. We should celebrate it more.

Chiruvella Pardha Krishna

18 February, 2026 03:59 AMThe naming convention is a metaphysical artifact of scientific reductionism. It strips the soul of the molecule to serve the algorithm of utility. Yet paradoxically, this very dehumanization preserves human life. The irony is not lost on those who understand that order is the last refuge of meaning in chaos.

Kapil Verma

18 February, 2026 08:29 AMUSAN is just American arrogance dressed up as science. Why does the U.S. get to keep 'acetaminophen' while the rest of the world uses 'paracetamol'? It's not tradition-it's isolationism. India and China don't need your colonial naming habits. INN should be mandatory worldwide, no exceptions.

Michael Page

19 February, 2026 00:45 AMI find it fascinating how the prefix is arbitrary. 'Ome-' in omeprazole. 'Ese-' in esomeprazole. It's like naming a child 'Zyphor' because it sounded cool. But then the stem does all the heavy lifting. The system is elegant in its indifference to aesthetics.

Mandeep Singh

20 February, 2026 07:52 AMYou people have no idea how much this matters. I work in a rural clinic in Bihar. Patients come in with bottles from Dubai, Germany, the U.S.-all different names. But once you learn the stems? You can tell what it does even if you've never seen the bottle before. This isn't bureaucracy. This is survival. And you're sitting there talking about 'elegance'? Wake up. This keeps people alive. No drama. Just facts.

Josiah Demara

22 February, 2026 07:29 AMLet’s be real-the naming system is a glorified game of Jenga with human lives. 40% of proposed names get rejected? That’s not precision. That’s overcorrection. And 'acetaminophen' vs. 'paracetamol'? That’s not history. That’s a fucking liability. One typo. One misread. One confused nurse. And boom. You’ve got a dead patient. This system is a house of cards held together by inertia and bureaucracy. We need a blockchain-based, AI-audited naming protocol. Now.

Sarah Barrett

24 February, 2026 02:13 AMThe fact that a drug’s name doesn’t change even if its use does is quietly brilliant. It means the science stays anchored. A molecule doesn’t care if it’s treating GERD or a peptic ulcer. Its action is constant. The name should reflect that. Not the marketing. Not the trend. The chemistry. That’s why this works.

Erica Banatao Darilag

25 February, 2026 04:47 AMI just wanted to say thank you for explaining this so clearly. I’ve been a pharmacist for 12 years and I still get confused sometimes. This helped me explain it to my niece who’s studying med school. She’s now obsessed with drug stems. I’m so proud.

ps: i hope i spelled everything right lol

Charlotte Dacre

26 February, 2026 12:00 PMSo let me get this straight. We spend 18 months arguing over whether a drug should be called 'lumiflozin' or 'lumifluzin'... so we don't accidentally kill someone because they mixed up 'Zoloft' and 'Zyloft'?

Yup. That's the American healthcare system in a nutshell.