Ulcer Risk Assessment Tool

Medication Risk Factors

Lifestyle Factors

Your Personalized Risk Assessment

Enter your risk factors to see your results

Key Takeaways

- Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the biggest culprits, raising ulcer risk by up to 5‑times.

- Corticosteroids, SSRIs, bisphosphonates, and certain anticoagulants also tip the odds, especially when combined with NSAIDs.

- Understanding the dose, duration, and personal risk factors helps you prevent painful sores.

- Proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers can offset medication‑induced damage when used wisely.

- If you’re on any of the listed drugs, talk to your doctor about protective strategies.

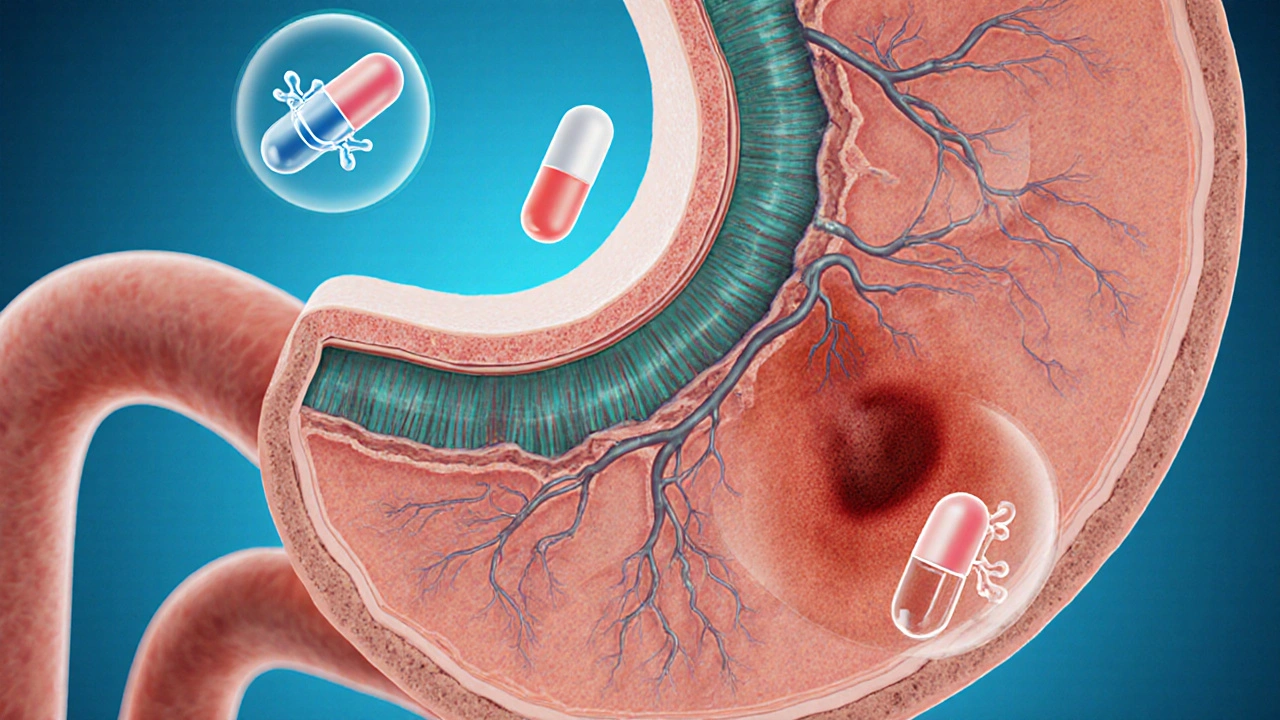

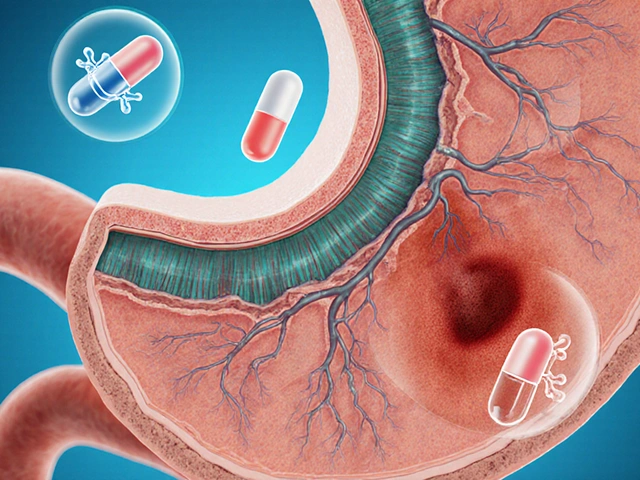

When people hear the term Peptic ulcer is a painful sore that forms on the lining of the stomach or duodenum, often caused by excess acid or infection, they assume it’s just a “stomach ache.” The truth is that many everyday medicines can damage the gut lining enough to spark an ulcer. In this guide we unpack which pills are the troublemakers, how they do it, and what you can do to stay safe.

First, let’s get clear on the biology. The stomach walls are protected by a thin mucus layer and a steady flow of bicarbonate that neutralizes acid. When a drug interferes with either mucus production or blood flow to the lining, the acid can eat away, creating a sore. That’s the core mechanism behind most medication‑related ulcers.

One class stands out: Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These include over‑the‑counter pain relievers and prescription anti‑inflammatories. By blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, NSAIDs reduce prostaglandins-substances that boost mucus and maintain blood flow. The result? A thinner protective barrier and a higher chance of bleeding. Studies from the American Journal of Gastroenterology show that regular NSAID users have a 3‑ to 5‑fold increase in ulcer incidence compared with non‑users.

Below are the most common NSAIDs and their relative ulcer risk numbers, pulled from a 2023 meta‑analysis of 12,000 patients:

| Medication | Class | Typical Use | Relative Risk Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | NSAID | Cardioprotection, pain | 150 |

| Ibuprofen | NSAID | OTC pain reliever | 200 |

| Naproxen | NSAID | Arthritis, pain | 180 |

| Corticosteroids (e.g., Prednisone) | Steroid | Inflammatory diseases | 120 |

| SSRIs (e.g., Fluoxetine) | Antidepressant | Depression, anxiety | 80 |

| Bisphosphonates (e.g., Alendronate) | Bone‑strengthener | Osteoporosis | 70 |

| Warfarin | Anticoagulant | Blood‑clot prevention | 60 |

The numbers above show that ulcer risk medications are not limited to painkillers. Even drugs that seem unrelated to the stomach can tilt the balance.

Corticosteroids are another frequent offender. They suppress inflammation by dampening the immune response, but they also impair the stomach’s ability to produce protective mucus. When taken at high doses or for long periods, corticosteroids can double ulcer rates on their own-and triple them when paired with an NSAID.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are best known for lifting mood, yet they affect platelets, reducing clotting ability. A thinned clotting response means even tiny mucosal injuries can bleed, turning a minor irritation into a full‑blown ulcer. A 2022 cohort study found a 1.8‑fold increase in ulcer hospitalization among SSRI users versus non‑users.

Bisphosphonates, the cornerstone of osteoporosis treatment, are taken with a full glass of water and an upright posture to avoid esophageal irritation. If that protocol is ignored, the drug can cause direct chemical burns in the esophagus, sometimes extending into the stomach and forming ulcers. The risk spikes to about 70% higher when patients skip the post‑dose water or lie down too soon.

Anticoagulants such as Warfarin (a vitamin K antagonist that thins the blood to prevent clots) don’t create ulcers themselves, but they prevent existing lesions from sealing. If you’re already on a NSAID or steroids, adding warfarin can push bleeding risk into dangerous territory.

How to Tell If a Drug Is Putting You at Risk

- Check the label for NSAID, steroid, or anticoagulant warnings.

- Ask your pharmacist whether the medication interferes with prostaglandin production.

- Track any new stomach pain, especially after meals or at night.

- Know your personal risk factors: H. pylori infection, smoking, alcohol, and a history of ulcers.

- Schedule a brief endoscopic check if you’ve been on high‑risk meds for more than three months.

Early detection can save you from surgery or chronic pain. If you notice dark stools, persistent nausea, or a gnawing ache, call your doctor right away.

Protective Strategies You Can Use

Not all hope is lost. Physicians often prescribe gastro‑protective agents alongside risky meds. The two most common are:

- Proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as omeprazole-these block acid production at its source.

- H2‑blockers like ranitidine-these reduce acid output but are slightly less potent than PPIs.

Research in the New England Journal of Medicine (2024) shows that adding a daily PPI cuts NSAID‑related ulcer risk by about 70%. However, long‑term PPI use isn’t free of side effects; talk with your doctor about the shortest effective course.

Another simple tactic: take the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration. For instance, if you need ibuprofen for a dental procedure, a single 400mg dose is far less risky than a 1,200mg daily regimen for weeks.

When to Switch Medications

If you’re on chronic NSAIDs for arthritis, ask about alternatives like acetaminophen (which has a much lower ulcer profile) or topical NSAIDs that stay on the skin and bypass the stomach. For chronic pain, some doctors now favor COX‑2 selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) because they spare the stomach lining-though they carry their own cardiovascular warnings.

Patients on SSRIs who develop ulcer symptoms might be switched to a different class of antidepressant, such as bupropion, which has no known impact on platelet function. Always discuss any change with a healthcare professional to avoid withdrawal or relapse.

Key Lifestyle Tweaks to Lower Your Overall Ulcer Risk

- Quit smoking - nicotine reduces mucus and impairs healing.

- Limit alcohol - especially when combined with NSAIDs.

- Maintain a balanced diet - fiber‑rich foods help protect the gut lining.

- Stress management - chronic stress can increase gastric acid output.

- Test for H. pylori - eradication therapy removes a major ulcer cause.

These habits complement any medication adjustments and give your stomach the best chance to stay healthy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can occasional ibuprofen cause an ulcer?

A single dose is unlikely to cause a lasting ulcer, but repeated use-even a few times a week-can start to wear down the protective mucus, especially if you have other risk factors.

Do PPIs guarantee I won’t get an ulcer while on NSAIDs?

PPIs dramatically lower the risk, but they don’t eliminate it. High‑dose NSAIDs or a combination with steroids can still breach the barrier.

Are aspirin‑free pain relievers safer for the stomach?

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) does not affect prostaglandins, so it’s generally gentler on the stomach. However, it can stress the liver at high doses.

Can I take a proton‑pump inhibitor without a prescription?

Many PPIs are available over the counter, but long‑term use should be guided by a doctor to avoid nutrient deficiencies and other side effects.

What signs suggest an ulcer has formed?

Persistent gnawing pain, especially a few hours after meals, dark or tarry stools, vomiting blood, and unexplained weight loss are red flags that need prompt medical evaluation.

Bottom line: not every medication will cause an ulcer, but a surprisingly large group does. By recognizing the high‑risk drugs, monitoring symptoms, and using protective strategies, you can keep your gut healthy while still treating the conditions you need medication for.

Alexia Rozendo

13 October, 2025 21:20 PMWow, looks like every drug manufacturer decided to throw safety out the window, huh?

Matt Laferty

17 October, 2025 10:00 AMWhen you consider the cascade of events that a non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug can trigger, the picture becomes almost cinematic in its drama. First, COX‑1 inhibition knocks down the prostaglandin shield that normally batters acid away from the mucosa. Then, without that protective mucus, the gastric epithelium is exposed to harsh hydrochloric acid, which begins a slow erosion. This erosion, if unchecked, can evolve into a full‑blown ulcer that bleeds, perforates, or leads to chronic pain. The literature repeatedly shows that even short courses of ibuprofen at 400 mg can increase risk by roughly 150 % in susceptible individuals, especially when combined with steroids. Adding a corticosteroid like prednisone compounds the problem, because steroids further suppress mucosal blood flow and impede healing. If you stack a PPI on top of that, you’ll see a roughly 70 % reduction in acid output, but the ulcer‑forming process may still continue under the radar. Moreover, SSRIs, through platelet dysfunction, impair clot formation, making even a tiny mucosal breach dangerous. In practice, the safest regimen is to employ the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration, and to pair any high‑risk NSAID with a gastro‑protective agent like omeprazole or a H2 blocker. Regular monitoring-checking for occult blood in stools or subtle dyspepsia-can catch problems early. For those who need chronic pain control, consider COX‑2 selective inhibitors, which spare the stomach lining but carry cardiovascular warnings. Patients on bisphosphonates should always remain upright for at least 30 minutes and ingest a full glass of water to avoid esophageal irritation. Finally, lifestyle adjustments-quitting smoking, limiting alcohol, and eradicating H. pylori-provide a solid foundation that works synergistically with any pharmacologic protection. In short, knowledge, moderation, and proactive shielding are the holy trinity for preserving gut health while still treating underlying conditions.

Kimberly Newell

20 October, 2025 22:39 PMGreat breakdown! Just wanted to add that if you’re takin any of these meds, try to keep a daily journal of your stomach feels. Even a small note about a twinge after lunch can help you and your doc catch a problem early. And don’t forget to ask your pharmacist about a PPI-sometimes they can suggest a cheaper generic that works just as well. Also, if you’re on a bssic regimen, you might want to double‑check the dosage instructions-typos happen all the time, like 500 mg instead of 50 mg. Stay safe and keep track of your meds, it’ll definitely pay off!

Drew Burgy

24 October, 2025 11:18 AMLook, the pharma giants love to hide the fact that they’re deliberately engineering these drugs to be “just effective enough” while maximising profit. They know full well that COX‑1 inhibition will chew up your gut lining, but they push it anyway because the market loves painkillers. It’s not a coincidence that you see the same “low‑risk” warnings plastered on the side of the bottle while the fine print mentions a “potential for ulcer formation” in a paragraph no one reads. And don’t even get me started on SSRIs; they’re marketed as mood lifters while silently turning your platelets into mush. If you think it’s just a side‑effect you can ignore, think again-big pharma is counting on you to stay sick enough to keep buying their next‑generation “safer” concoctions.

Johnna Sutton

27 October, 2025 22:57 PMPatriotically speaking, the United States has a responsibility to protect its citizens from such corporate greed, yet we see regulatory capture at its finest. While the FDA grants approvals with glossy press releases, the underlying data often shows an alarming increase in ulcer‑related hospitalizations following the launch of new NSAID formulas. The irony is that American‑made medications sometimes claim a “made‑in‑USA” badge, but the safety standards are no better than abroad, especially when lobbyists influence policy. It’s almost as if the very institutions meant to safeguard public health have become extensions of the pharmaceutical lobby, allowing dangerous combos like NSAID‑plus‑steroid to be marketed without stringent warnings. This is a call for citizens to demand transparent data and stricter oversight-otherwise, we’re just signing up for a national health crisis.

Genie Herron

31 October, 2025 11:36 AMI feel sooo sad when I read about people suffering from ulcers it just breaks my heart I wish there was a magical pill that could protect everyone from pain

Lisa Lower

4 November, 2025 00:15 AMListen up everyone – you have the power to take control of your gut health right now! Start by reviewing every prescription you take, ask for the lowest effective dose, and demand a protective PPI if you can’t avoid NSAIDs. No more sitting around hoping it won’t happen – be proactive, set reminders, and keep a simple log of any stomach discomfort. You’re stronger than those side‑effects, and together we can push back against unnecessary risk. Let’s do this!

Dana Sellers

7 November, 2025 12:55 PMHonestly, it’s just common sense. If you’re popping pills that can burn your stomach, you should be taking steps to protect yourself. No excuses.

Damon Farnham

11 November, 2025 01:34 AMIndeed-while the preceding statements exude commendable zeal, one must also consider the nuanced pharmacodynamics at play; the mere act of “popping pills,” as colloquially phrased, fails to capture the intricacies of dosage‑response relationships, metabolic variability, and the pivotal role of gastric mucosal integrity, which, when compromised, precipitates a cascade of pathophysiological events-an outcome that demands a judicious, evidence‑based approach, rather than simplistic admonishment.

Justin Park

14 November, 2025 14:13 PMContemplating the delicate balance of gastric protection feels like a philosophical riddle: how do we reconcile the necessity of pain relief with the sanctity of our bodily integrity? 🤔 It’s a dance of risk and reward, and each choice sways the rhythm of our health.

nathaniel stewart

18 November, 2025 02:52 AMIndeed, your riddle is quite profound. In a world where we attend to the minutia of daily life, we often overlook the complex interplay of medication pharmacokynetics and mucosal defence. I wholeheartedly encourge further discourse on balancING these crucial aspects.

Pathan Jahidkhan

21 November, 2025 15:31 PMAh, the drama of the gut! One might say it’s a stage where the hero- our humble stomach- is constantly besieged by villainous pills, yet the audience- us- seldom notices the tragedy until the curtain falls. Such is the lazy critic’s lament.

Dustin Hardage

25 November, 2025 04:10 AMWhile the metaphorical stage is vivid, let’s ground the discussion in evidence‑based practice: assessing ulcer risk requires a systematic review of medication lists, dosage, duration, and patient‑specific factors such as H. pylori status. Proactive measures, including prescribing a PPI when indicated and counseling on lifestyle, are essential components of a comprehensive care plan.

Manish Singh

28 November, 2025 16:50 PMThank you for the clear guidance. I’ve seen patients feel overwhelmed, so breaking it down into simple steps-list meds, check doses, add protection, and monitor-really helps them feel empowered.

Dipak Pawar

2 December, 2025 05:29 AMFrom a cultural perspective, the discourse surrounding ulcerogenic medications often intersects with sociomedical paradigms that prioritize acute symptom relief over chronic gastrointestinal stewardship. In many healthcare ecosystems, especially those navigating limited resources, the prescription of NSAIDs without adjunctive gastro‑protective strategies is not merely a clinical oversight but a reflection of systemic exigencies that demand cost‑effective yet safe therapeutic algorithms. By integrating pharmacoeconomic analyses with patient‑centered outcomes, clinicians can devise regimens that harmonize efficacy with mucosal preservation, thereby mitigating the burden of ulcer disease across diverse populations.