When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it actually does? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most widely used method to prove that a generic drug behaves the same way in your body as the original. Yet calling it the "gold standard" is misleading. It’s not perfect. It’s not always enough. And for some drugs, it’s barely even the best option.

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

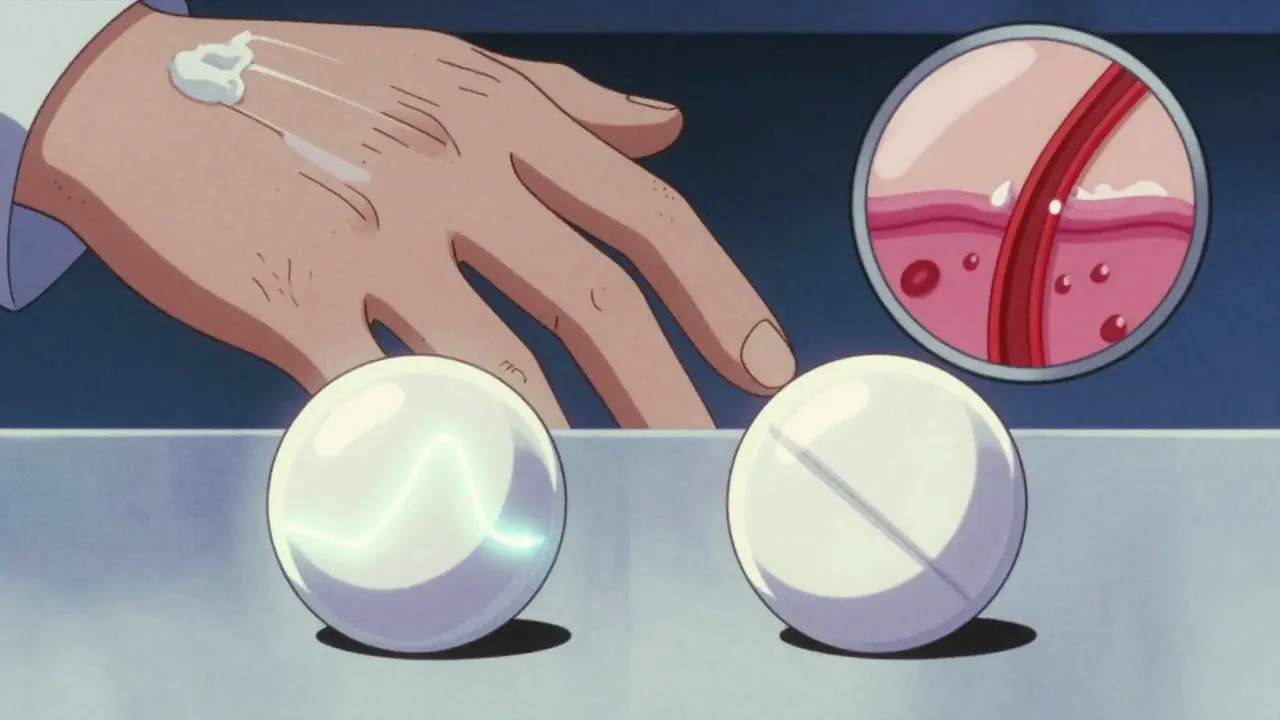

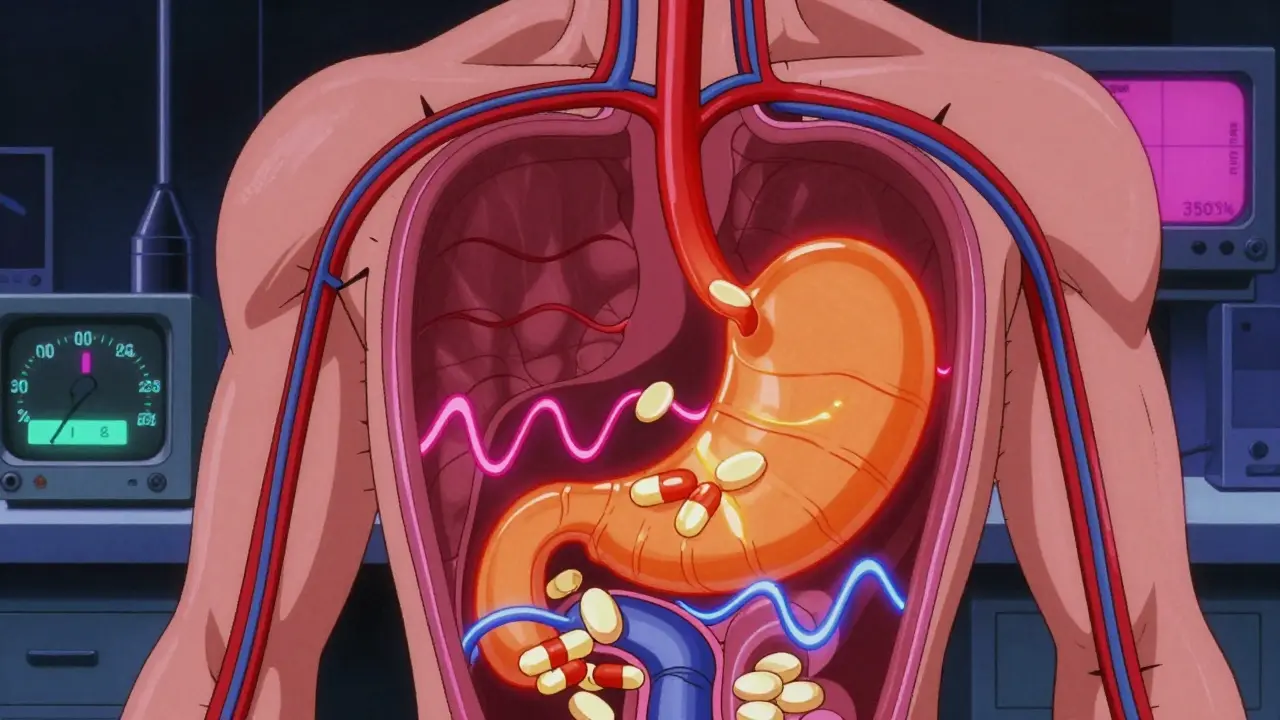

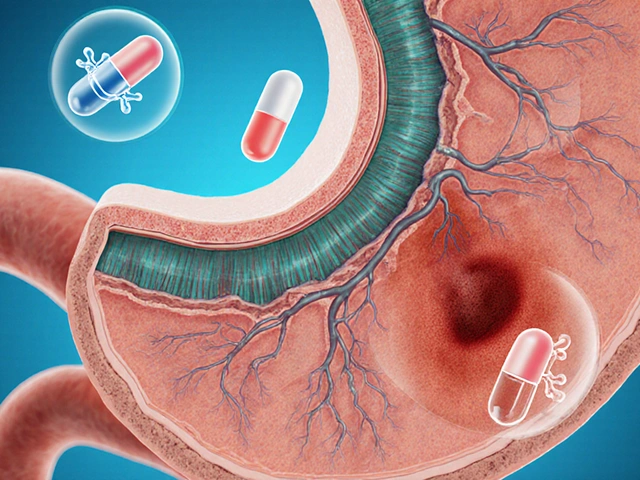

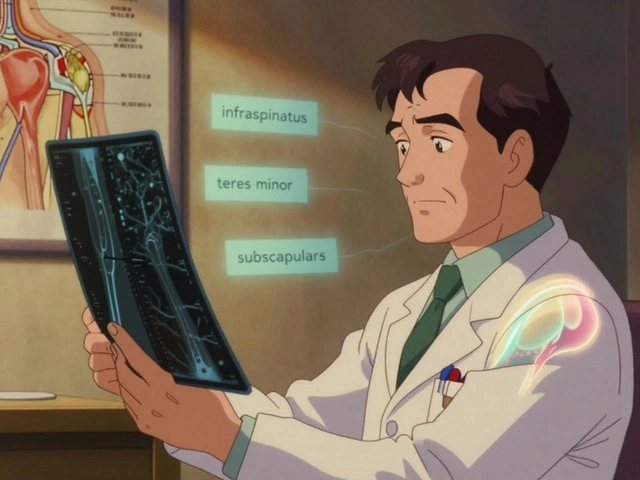

Pharmacokinetic studies track how your body handles a drug after it’s taken. They focus on two key numbers: Cmax and AUC. Cmax is the highest concentration of the drug in your blood. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body absorbs over time. Together, they show how fast and how completely the drug gets into your system. These studies are done in healthy volunteers, usually between 24 and 36 people. Each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic version at different times, in a randomized order. This is called a crossover design. The goal? To see if the generic’s Cmax and AUC fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s values. If they do, regulators consider the two drugs bioequivalent. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, phenytoin, or digoxin-the rules get tighter. The acceptable range shrinks to 90% to 111%. That’s because even small differences in absorption can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure. These are not hypothetical risks. Real patients have been harmed when generics didn’t match the original closely enough.Why Pharmacokinetic Studies Are the Default

The reason these studies dominate is simple: efficiency. Before 1984, companies had to run full clinical trials to prove a generic drug worked. That meant thousands of patients, years of testing, and millions of dollars. The Hatch-Waxman Act changed that. It allowed generic makers to skip costly clinical trials if they could prove bioequivalence through pharmacokinetics. Today, the FDA approves about 95% of generic drugs based on this method. It’s fast, cheaper, and scientifically sound-for many drugs. A 2010 study in PLOS ONE found failure rates below 2% for standard immediate-release oral medications. That’s impressive. It means for most pills you take daily-antibiotics, blood pressure meds, antidepressants-pharmacokinetic studies reliably predict that the generic will work just as well. But here’s the catch: this method only works if the drug is absorbed into your bloodstream. It doesn’t tell you anything about what happens after that. If a drug acts locally-like an asthma inhaler, a skin cream, or an eye drop-measuring blood levels tells you almost nothing.The Limits of Blood Tests for Topical and Complex Drugs

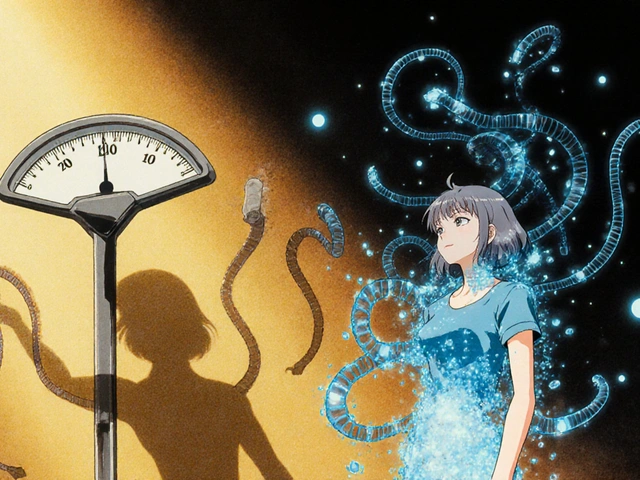

Think about a steroid cream for eczema. You apply it to your skin. The goal isn’t to get it into your blood. It’s to get it into the top layers of your skin to reduce inflammation. A pharmacokinetic study measuring plasma concentrations? Useless. You’d need to measure drug levels in the skin itself. That’s where dermatopharmacokinetic (DMPK) methods and in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) come in. These techniques use human skin samples-often cryopreserved-to see how much of the drug actually penetrates. A 2014 study by Lehman and Franz showed IVPT was more accurate and less variable than clinical trials for semisolid drugs. In 2019, Senemar et al. proved DMPK could detect differences between formulations with over 90% power. Yet, most regulators still require pharmacokinetic data for these products. Why? Because it’s the only method they’ve standardized. The result? Generics for topical drugs are approved based on data that doesn’t reflect how the drug actually works. Even more troubling: two generics can have identical chemical composition, identical dissolution rates in a lab, and still behave differently in the body. A 2010 PLOS ONE study showed that two generics of gentamicin-made by reputable companies, meeting all pharmaceutical equivalence standards-had wildly different therapeutic effects. The blood levels looked fine. The clinical outcome didn’t. That’s not a failure of testing. It’s a failure of assumptions.

When the Lab Test Isn’t Enough

Some drugs are so complex that even pharmacokinetic studies can’t predict real-world performance. Modified-release tablets, for example, are designed to release the drug slowly over hours. Change the shape of the tablet, the type of coating, or even a minor excipient, and the release profile shifts. The drug might still reach the same blood concentration-but at the wrong time. That can mean ineffective dosing or dangerous spikes. Manufacturers spend $300,000 to $1 million per bioequivalence study. It takes 12 to 18 months. And for many of these complex products, that’s still not enough. The FDA now has 1,857 product-specific guidances for different drugs. That’s not a sign of a robust system. It’s a sign of a system that’s constantly patching holes. This is why the FDA launched its Complex Generic Drug Products Initiative in 2018. It’s an acknowledgment that the old rules don’t fit new realities. For some drugs, they’re now accepting physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. This uses computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves based on its chemical properties, body physiology, and formulation. It’s faster, cheaper, and sometimes more accurate than human trials.Global Differences and Regulatory Chaos

The U.S. FDA, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the WHO all agree on the goal: therapeutic equivalence. But they don’t agree on how to get there. The FDA uses product-specific guidelines. If you’re making a generic of a particular brand, you follow the exact protocol for that drug. The EMA, by contrast, often uses a one-size-fits-all approach. That creates headaches for global manufacturers. A generic approved in the U.S. might be rejected in Europe because the equivalence limits or study design don’t match. And then there are emerging markets. About 50 countries follow international bioequivalence standards, but many lack the labs, trained staff, or funding to run proper studies. The result? Generics enter the market with little oversight. Patients get pills that look the same but don’t act the same.What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The field is moving beyond blood tests. For some drugs, in vitro testing is proving more reliable than in vivo studies. For others, PBPK modeling is replacing human trials entirely. The FDA has already accepted PBPK waivers for certain BCS Class I drugs-those that dissolve easily and are absorbed quickly. The future isn’t about one method being the "gold standard." It’s about matching the right tool to the right drug. For a simple tablet? Pharmacokinetic studies still work. For a complex inhaler? Maybe in vitro testing. For a topical gel? DMPK. For a slow-release capsule? PBPK modeling. The real gold standard isn’t a test. It’s patient outcomes. If a generic drug doesn’t keep someone’s blood pressure stable, or triggers seizures in someone with epilepsy, it doesn’t matter how perfect the blood levels look.Why This Matters to You

You might think this is just a regulatory issue. But it’s personal. If you take a generic for a critical condition-epilepsy, heart arrhythmia, thyroid disease-you’re relying on this system to keep you safe. When it works, it saves money and lives. When it fails, the consequences can be devastating. The good news? For most people, generics are safe and effective. The system works well for the majority of drugs. But you should know: not all generics are created equal. And the science behind them is far from settled. Ask your pharmacist if the generic you’re taking has been tested specifically for your condition. If you notice a change in how you feel after switching-fatigue, dizziness, reduced effectiveness-don’t brush it off. Talk to your doctor. It might not be in your head. It might be in the tablet.Are pharmacokinetic studies always accurate for proving generic drug equivalence?

No. Pharmacokinetic studies are accurate for many oral drugs that enter the bloodstream, like antibiotics or blood pressure pills. But they’re unreliable for topical creams, inhalers, eye drops, and some complex formulations. In those cases, the drug doesn’t need to reach the blood to work, so measuring plasma levels tells you nothing about its real effect. Studies have shown that even generics with identical blood profiles can have different clinical outcomes.

What is the 80-125% rule in bioequivalence testing?

It’s the range regulators use to decide if a generic drug is absorbed similarly to the brand-name version. If the generic’s maximum blood concentration (Cmax) and total absorption (AUC) fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s values, it’s considered bioequivalent. This applies to most standard oral drugs. For high-risk drugs like warfarin or digoxin, the range is tighter-90% to 111%-because small differences can cause serious side effects.

Why are pharmacokinetic studies so expensive and time-consuming?

A single bioequivalence study costs between $300,000 and $1 million and takes 12 to 18 months. That’s because it requires recruiting healthy volunteers, conducting multiple dosing sessions under strict controls, collecting blood samples over hours or days, and running detailed lab analyses. The process must be repeated for both fasting and fed conditions if the drug’s absorption is affected by food. For complex drugs, additional studies may be needed, driving costs even higher.

Can in vitro tests replace human pharmacokinetic studies?

Yes, in some cases. For immediate-release drugs with good solubility and permeability (BCS Class I), well-designed in vitro dissolution tests can predict bioequivalence just as well-or better-than human trials. For topical products, in vitro permeation testing using human skin has proven more accurate and consistent than clinical endpoint studies. The FDA now accepts these methods for certain drugs, especially when they’re validated and standardized.

What are narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, and why do they need stricter testing?

NTI drugs have a very small margin between an effective dose and a toxic one. Examples include warfarin (blood thinner), phenytoin (anti-seizure), and digoxin (heart medication). A slight increase in absorption can cause bleeding, seizures, or heart failure. A slight decrease can make the drug useless. That’s why regulators require tighter bioequivalence limits-90% to 111% instead of 80% to 125%-and sometimes additional clinical monitoring for these drugs.

Christopher King

26 December, 2025 01:42 AMLet me tell you something they don't want you to know. The FDA doesn't test generics for real-world effectiveness - they test them for blood levels. That's it. And who funds the studies? The same pharma companies making the generics. There's a whole shadow network of contract labs that cook the data. I've seen the spreadsheets. Cmax? AUC? Just numbers on a screen. What about how the drug actually makes you feel? What about the guy who switched to generic warfarin and ended up in the ER? They call it bioequivalence. I call it corporate fraud with a lab coat.

And don't even get me started on the WHO. They push these standards on poor countries like India and Nigeria. They hand out pills that look identical but don't work. People die. And the regulators? They shrug. It's not their problem. It's always someone else's fault. The system is rigged. And you're all just sheep waiting for your next pill.

Wake up. This isn't science. It's a profit-driven illusion. They don't care if you live or die. They care if the stock price goes up. You think your blood test means safety? It means they passed the paperwork. That's all.

Next time you pick up a generic, ask yourself - who really benefits here? Not you. Not your body. Not your health. It's the shareholders. Always the shareholders.

Bailey Adkison

27 December, 2025 23:07 PMPharmacokinetic studies are not the gold standard because they're perfect. They're the default because they're the only standardized method that works at scale. The 80-125% range is statistically validated across millions of prescriptions. The failure rate for simple oral drugs is under 2%. That's not a flaw. That's a feature.

Yes there are edge cases. Topical drugs. Complex release formulations. NTI drugs. But those are exceptions. You don't throw out the entire system because a few edge cases exist. That's like banning cars because snow tires don't work on ice.

And yes PBPK modeling is promising. But it's not ready for prime time. It's still being validated. Until then we use what works. Not what sounds sexy in a journal article.

Stop pretending regulators are incompetent. They're not. They're just conservative. And that's a good thing when people's lives are on the line.

Michael Dillon

28 December, 2025 06:55 AMLook I get the concerns. But here's the reality - if you're on a generic for high blood pressure or antibiotics and you're not having issues, it's working. The system isn't perfect but it's working better than almost any other regulatory framework out there.

The $300k studies? Yeah they're expensive. But they're cheaper than running clinical trials on 10,000 patients. And guess what? We've had over 40 years of real-world data. Millions of people. Billions of doses. The failure rate is microscopic.

And yes for inhalers or creams we need better methods. That's why the FDA is already moving toward DMPK and IVPT. Progress isn't zero. It's just slow. And that's because safety comes first.

Stop treating every regulatory gap like a conspiracy. Most of these people are just trying to keep you alive without bankrupting the healthcare system.

Katherine Blumhardt

28 December, 2025 21:01 PMOMG I JUST REALIZED SOMETHING 😱

What if the generic pills are secretly programmed to make us drowsy so we don't notice how much the government is lying to us?? Like what if the fillers are actually microchips?? I read on a blog that the FDA gets paid by Big Pharma to approve bad generics and then they put tracking agents in the coating so they can monitor your heart rate from space??

I switched to organic herbal tea and now I feel 100% better. Also my cat started staring at me differently. Coincidence? I think not.

Also why do all the pills have the same shape?? That's not natural. That's control. 🤔

sagar patel

30 December, 2025 10:51 AMIndia makes over 60% of the world's generic drugs. We follow WHO guidelines. But we don't have the labs or the funding to do advanced testing. So we do what we can. The system isn't perfect but it's better than nothing. People here die without these drugs. So we give them the best we have.

Yes there are bad batches. Yes some companies cut corners. But most generics work. I've seen it. My father takes generic metformin. His sugar is stable. He doesn't need to pay $500 a month. That's not a failure. That's justice.

Stop romanticizing the brand-name pills. They're just the same chemistry with a fancy label and a higher price tag.

And yes we need better methods. But don't blame the poor countries trying to survive. Blame the system that lets rich nations hoard innovation while the rest beg for pills.

Linda B.

30 December, 2025 20:24 PMHow convenient that the very same regulators who approved Vioxx and OxyContin now tell us pharmacokinetics is "scientifically sound."

Let's be clear - this isn't about science. It's about cost-cutting disguised as efficiency. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a corporate gift wrapped in the language of public health. And now we're told to trust blood levels while ignoring clinical outcomes.

Meanwhile, the FDA quietly accepts PBPK models for BCS Class I drugs - the ones that are easy to fake. But for the complex ones? Keep the old flawed system. Because if you change it, you'd have to admit you were wrong for 40 years.

And don't even mention the 50 countries with zero oversight. That's not a gap. That's a massacre.

They call it bioequivalence. I call it calculated risk. And the patient? Just the collateral.

Terry Free

31 December, 2025 22:55 PMLet’s be honest - if your generic isn’t working, it’s probably not the drug. It’s you. You’re psychosomatic. You’re anxious. You’re overthinking. You switched from brand to generic and now you’re convinced your body is failing. It’s not. Your mind is.

Pharmacokinetics measures absorption. Absorption = bioavailability. Bioavailability = therapeutic potential. That’s not a theory. That’s pharmacology 101.

And yes, for topical drugs, we need better tools. But we’re building them. The FDA’s Complex Generic Initiative is real. It’s not a conspiracy. It’s a program with a budget and peer-reviewed papers.

Stop treating every regulatory compromise like a moral failing. Science doesn’t move at the speed of your outrage.

Sophie Stallkind

1 January, 2026 07:08 AMThank you for this comprehensive and nuanced analysis. The tension between regulatory pragmatism and scientific rigor is rarely discussed with such clarity. The recognition that bioequivalence is not synonymous with therapeutic equivalence is critical.

For patients on narrow therapeutic index medications, the current system's limitations are not abstract - they are life-altering. The fact that two generics with identical pharmacokinetic profiles can yield divergent clinical outcomes underscores the urgent need for outcome-based endpoints in regulatory frameworks.

While pharmacokinetic studies remain a necessary and valuable tool for the majority of oral solid dosage forms, their extension to non-systemic or complex formulations represents a significant scientific and ethical gap. The FDA's adoption of PBPK and in vitro methods for select products is a promising step, but must be accelerated and standardized globally.

Ultimately, patient outcomes must become the primary metric - not the convenience of testing protocols. The system must evolve to reflect the complexity of human physiology, not the simplicity of regulatory convenience.