When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. You’re not just saving money-you’re trusting the system to keep you safe. But what if that trust is being manipulated? False advertising in generic pharmaceuticals isn’t just a shady marketing tactic-it’s a legal minefield with real health consequences.

What Counts as False Advertising in Generic Drugs?

False advertising in generic drugs happens when a company makes claims that aren’t backed by science or violate FDA rules. This isn’t about minor wording. It’s about saying things like:- "Our generic is just as good as the brand-better, even."

- "The brand has hidden side effects our version doesn’t."

- "FDA Approved" when the product only has "FDA Clearance."

- Using visuals or jingles that make your generic look exactly like the brand-name drug.

The Legal Framework: More Than Just FDA Rules

The rules aren’t just one agency’s opinion. They’re backed by federal law. The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) of 1938 is the backbone. It bans false or misleading labeling and advertising. Then there’s the Lanham Act, which lets competitors sue each other for deceptive marketing. That’s important. It means if your rival runs an ad claiming their generic is safer or more effective, you can take them to court-not just the FDA. In 2025, the U.S. government cracked down hard. A presidential memorandum directed the Department of Health and Human Services to target ads that "inappropriately intervene in the physician-patient relationship" and "advantage expensive drugs over cheaper generics." That’s a direct shot at companies using fear tactics to push brand-name drugs. The FDA issued 100 cease-and-desist letters just in September 2025, mostly targeting misleading comparisons between brand and generic drugs. State laws add another layer. California’s Unfair Competition Law and New York’s General Business Law § 349 allow consumers to sue for damages. In New York, courts can award three times the actual damages, up to $1,000 per violation. That’s not a fine. That’s a lawsuit waiting to happen.The Big Loophole That Got Closed

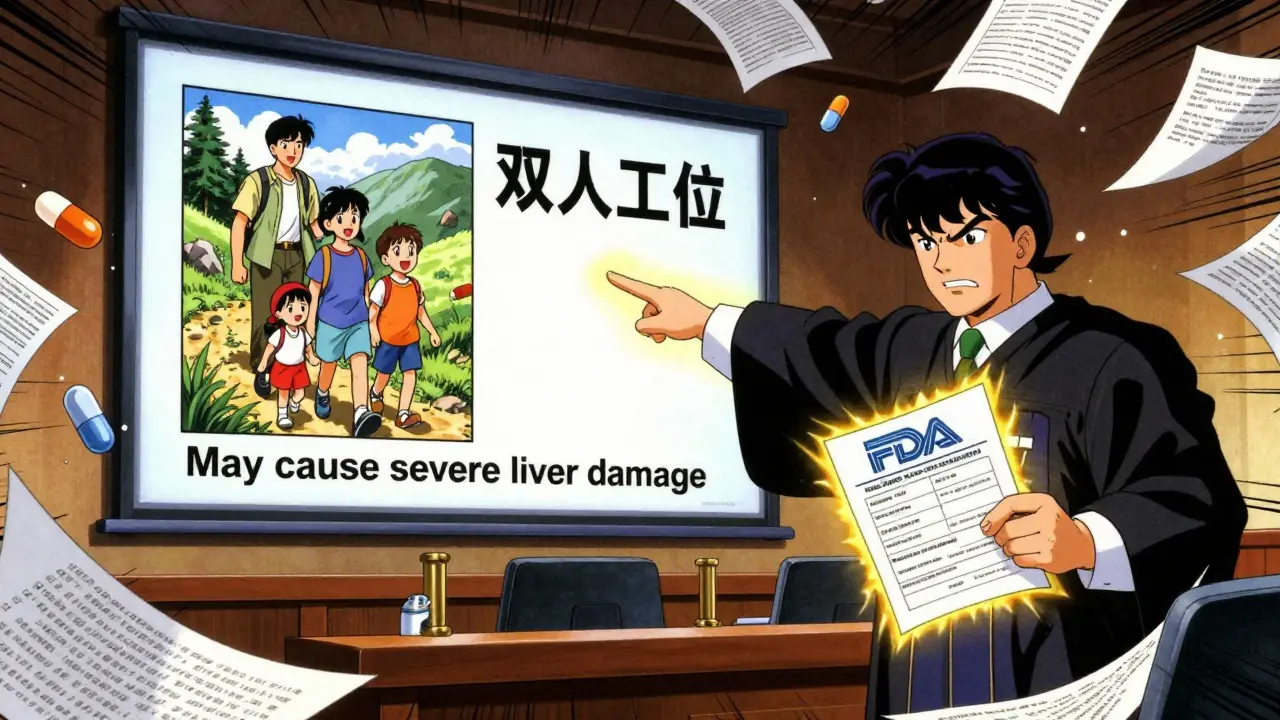

For decades, drug ads could say something like: "For complete risk information, visit [website]." This was called the "adequate provision" rule. It let companies bury the side effects in fine print or a link they hoped you’d never click. But in September 2025, the FDA killed that loophole. Now, every broadcast and digital ad must include all major risks right in the message. No hiding. No redirects. If your ad mentions a benefit, you must state the most serious side effects at the same time, in clear, readable text. That’s a game-changer. A 30-second TV spot can’t just show a smiling family hiking. It now needs to say: "This drug may cause severe liver damage. Stop use and call your doctor if you notice yellowing of skin or eyes." And it has to be in at least 14-point font with 50% contrast. No tiny text. No quick flashes. No sneaky editing.

Why Generic Ads Are Treated Differently Than Brand-Name Ads

Brand-name drug ads can talk about benefits, lifestyle improvements, and even compare themselves to other brand-name drugs. Generics? Not so much. They can’t claim superiority unless they’ve done head-to-head clinical trials-which most don’t. They can say they’re "lower cost," but they can’t say "you’ll save 65%" unless they can prove it with real pharmacy data. The FTC requires hard numbers, not estimates. Also, generics must clearly state: "This is a generic drug" and name the brand-name drug they’re copying. No hiding the fact that it’s not the original. Visuals matter too. If your ad uses the same color, shape, or logo as the brand, you’re risking confusion-and legal action. One company got hit with a Lanham Act lawsuit after running a digital ad that showed a pill with the same blue oval shape as the brand-name version. The court ruled it created consumer confusion, even though the generic’s name was visible. The company paid $2.3 million in damages.Real People, Real Harm

This isn’t just about legal fines. It’s about lives. In 2024, the FDA analyzed 1,247 patient complaints linked to misleading generic drug ads. Thirty-two percent of those patients stopped taking their medication because they believed the generic was unsafe. Many developed complications they could have avoided. On Reddit, a thread from March 2025 showed patients refusing levothyroxine generics after seeing YouTube ads claiming "generic thyroid meds cause heart problems." The FDA has repeatedly confirmed that these generics meet strict bioequivalence standards. But the fear stuck. Patients went back to the more expensive brand-because they were scared, not because it was better. Meanwhile, seniors who saw clear, honest ads from compliant companies reported 78% higher awareness of cost savings. That’s the other side. When done right, generic advertising helps people afford their meds.Who’s Responsible? The Compliance Team Inside Big Pharma

You don’t just slap together an ad and run it. Major generic manufacturers have entire teams-15 to 25 people-dedicated to making sure every word, image, and sound is legal. These teams include:- Regulatory affairs specialists (with 5+ years of FDA experience)

- Medical writers who understand clinical data

- Lawyers who know the Lanham Act inside out

- Graphic designers trained in FDA font and contrast rules

What Happens If You Get Caught?

The penalties aren’t light:- FDA Warning Letters: Public, posted online. Damages your reputation. Triggers investor concerns.

- Lanham Act Lawsuits: Competitors can sue for lost sales. Damages can be tripled.

- State Consumer Laws: In New York, up to $1,000 per violation, trebled.

- Reputational Damage: Once you’re labeled as deceptive, pharmacies and insurers may drop you.

- Product Recalls: If your ad implies safety issues, the FDA may force a recall-even if the drug is fine.

What Should You Do? A Checklist for Compliance

If you’re involved in marketing generic drugs, here’s what you need to do right now:- Never say "FDA Approved" unless the product has an ANDA approval. "FDA-Cleared" is not the same.

- Always state: "This is a generic version of [Brand Name]."

- Include all major risks in every ad. No links. No fine print.

- Don’t imply superiority unless you have head-to-head clinical trial data.

- Use clear, readable fonts (14-point minimum) with high contrast.

- Avoid visuals that mimic the brand-name product’s shape, color, or packaging.

- Never quantify savings without verified pharmacy pricing data.

- Train every team member on FDA Guidance for Industry (2023) and FTC advertising rules.

The Future Is Tighter Enforcement

The FDA and FTC are moving toward a unified system. Draft legislation called the "Transparency in Drug Advertising Act" is already in Congress. It would standardize risk disclosure rules across all media-TV, radio, social media, billboards. Industry analysts predict enforcement actions will rise 35% per year through 2027. Generic manufacturers are under the microscope. Companies that invest in compliance-like Pfizer’s $45 million review system-are staying ahead. Those cutting corners? They’re one ad away from a lawsuit that could shut them down. The message is clear: in generic drug advertising, truth isn’t just ethical-it’s the only way to stay in business.Can a generic drug be advertised as "better" than the brand-name version?

No. Generics cannot claim superiority unless they’ve conducted and published head-to-head clinical trials proving it. The FDA and FTC require scientific evidence for any comparative claim. Most generic manufacturers avoid this entirely because such trials are expensive and rarely necessary-bioequivalence is the legal standard, not superiority.

What’s the difference between "FDA Approved" and "FDA Cleared" for generics?

"FDA Approved" means the drug went through a full New Drug Application (NDA) process, which brand-name drugs use. Generics use the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. While ANDA approval is legally equivalent, the term "FDA Approved" is reserved for NDAs. Using it for generics is a violation. The correct term is "FDA-approved generic" or "ANDA-approved." Misusing this language has triggered multiple Lanham Act lawsuits.

Can generic drug ads mention cost savings?

Yes, but only if the savings are verifiable. You can say "lower cost" or "saves money," but you cannot say "save 70%" unless you can prove it with real-time pharmacy pricing data from multiple sources. The FTC requires all claims to be substantiated. Vague statements like "affordable alternative" are safe. Specific percentages are not.

Do I need to include side effects in digital ads?

Yes. As of September 2025, the FDA eliminated the "adequate provision" loophole. All digital, TV, and radio ads must include the most serious risks directly in the message. You can’t just link to a website. Side effects must be visible, readable, and presented with the same prominence as the benefits-minimum 14-point font, 50% contrast.

Can I use the same pill shape or color as the brand-name drug in my ad?

No. The FDA and courts have ruled that using identical or highly similar pill shapes, colors, or logos can create consumer confusion. Even if the drug is bioequivalent, the visual similarity may mislead patients into thinking the generic is the brand. This has led to lawsuits under the Lanham Act. Always use neutral, distinct visuals for generics.

What happens if a patient stops taking their generic because of a misleading ad?

If the ad caused the patient to discontinue a necessary medication and they suffered harm, the company behind the ad can be held liable. The FDA has documented over 400 cases since 2023 where patients experienced adverse outcomes after stopping generics due to fearmongering ads. These cases can lead to state consumer protection lawsuits, FDA enforcement, and even criminal liability if fraud is proven.

Are there any states with stricter rules than the FDA?

Yes. California’s Unfair Competition Law and New York’s General Business Law impose stricter substantiation requirements. Florida bans the use of government logos or terms like "health alert" in pharmaceutical ads. Companies running nationwide campaigns must comply with the strictest standard in each state-or risk penalties in multiple jurisdictions.

Elaine Douglass

20 December, 2025 10:24 AMI had a friend who stopped her generic thyroid med after seeing one of those fear-mongering YouTube ads. She ended up in the ER. No joke. I wish people would just check the FDA site before panicking.

It’s scary how much power a poorly made ad can have over someone’s health.

Takeysha Turnquest

21 December, 2025 07:08 AMTruth is a casualty of capitalism. We’ve turned medicine into a spectacle. Pills are no longer healing-they’re branded commodities.

And we let them.

What are we but consumers screaming for labels while our bodies decay in silence?

Emily P

21 December, 2025 21:44 PMSo if a generic can’t claim superiority without head-to-head trials, how do we even know which ones are actually reliable? Is there a public database somewhere that lists which generics have been tested beyond bioequivalence? I’ve never seen one.

Jedidiah Massey

23 December, 2025 01:04 AMLet’s be real-the FDA’s enforcement is performative at best. The Lanham Act is a toothless tiger when Big Pharma has 12 lawyers per compliance officer.

And don’t get me started on the FTC’s ‘verifiable’ savings standard-good luck getting real-time pharmacy data from CVS or Walgreens. It’s a farce wrapped in 14-point font.

:/

Allison Pannabekcer

24 December, 2025 22:59 PMThere’s a quiet heroism in the compliance teams working 18-month learning curves just to make sure a pill ad doesn’t kill someone.

Most people don’t realize how many people are quietly fighting to keep this system from collapsing.

It’s not glamorous. No one gets a trophy. But without them, someone’s grandparent stops taking their meds because a 30-second ad scared them.

We owe these folks more than silence.

Maybe we start by trusting the science, not the fear.

And if you’re a small company struggling to comply? You’re not alone. There are nonprofits helping. Reach out.

It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being responsible.

And yeah, visuals matter. If your pill looks like the brand, you’re already in trouble.

Even if you think it’s ‘just a color.’

It’s not just about law. It’s about dignity.

Everyone deserves to take their medicine without doubt.

Sarah McQuillan

26 December, 2025 00:13 AMWhy are we even letting the FDA dictate what generic ads can say? This is America. Let the market decide.

People should be able to choose if they want to believe the fear ads or not.

It’s not the government’s job to protect us from our own stupidity.

And besides, the brand-name companies are the ones lying with their ‘premium’ pricing.

Stop protecting monopolies under the guise of ‘safety.’

anthony funes gomez

27 December, 2025 12:10 PMConsider the semiotics of pharmaceutical advertising: the pill shape as signifier of authenticity, the color as cultural codex of efficacy, the font size as performative transparency-yet all of it is constrained by regulatory hegemony.

Is bioequivalence truly epistemological equivalence? Or are we merely enforcing aesthetic conformity under the guise of scientific rigor?

And who decides what constitutes ‘serious’ side effects? The FDA? Or the marketing department that wrote the script?

…I mean, really.

It’s all a performance.

Alana Koerts

28 December, 2025 05:59 AM1,247 patient complaints? That’s nothing.

Try 12 million Americans who’ve been scared off generics by YouTube ads.

And the FDA only issued 100 cease-and-desist letters? Pathetic.

They’re barely scratching the surface.

Also, ‘14-point font’? Please. I’ve seen ads where the risk text is smaller than the Instagram logo.

Lazy.

Mark Able

29 December, 2025 06:42 AMHey I work in pharma marketing and I gotta say-this post is spot on.

But here’s the real issue: most small generic companies don’t even know the rules exist.

They buy a template off Fiverr, slap on a blue pill, and run it on Facebook.

They don’t have legal teams. They’re single moms running a business.

So instead of just slapping fines on them, why not create free compliance toolkits?

Or partner with pharmacy schools to train them?

We could fix this if we actually wanted to.

Not punish. Educate.

William Storrs

31 December, 2025 06:03 AMYou’ve got this.

Every time you choose a generic, you’re not just saving money-you’re fighting for a fairer system.

And if you see a sketchy ad? Report it.

It’s not just about you.

It’s about the grandma who can’t afford the brand.

It’s about the kid who needs insulin.

It’s about dignity.

Keep speaking up.

You’re making a difference.

And if you’re a company reading this? Do the right thing.

It’s worth it.

Guillaume VanderEst

31 December, 2025 20:20 PMSo… the FDA just made it illegal to lie about pills?

Wow.

That’s… actually kind of wild.

Like, in 2025, we needed a law to stop companies from saying their medicine is ‘better’ when it’s literally the same chemical?

What even is this world?

…I mean, I guess it’s good.

But also… why did it take this long?