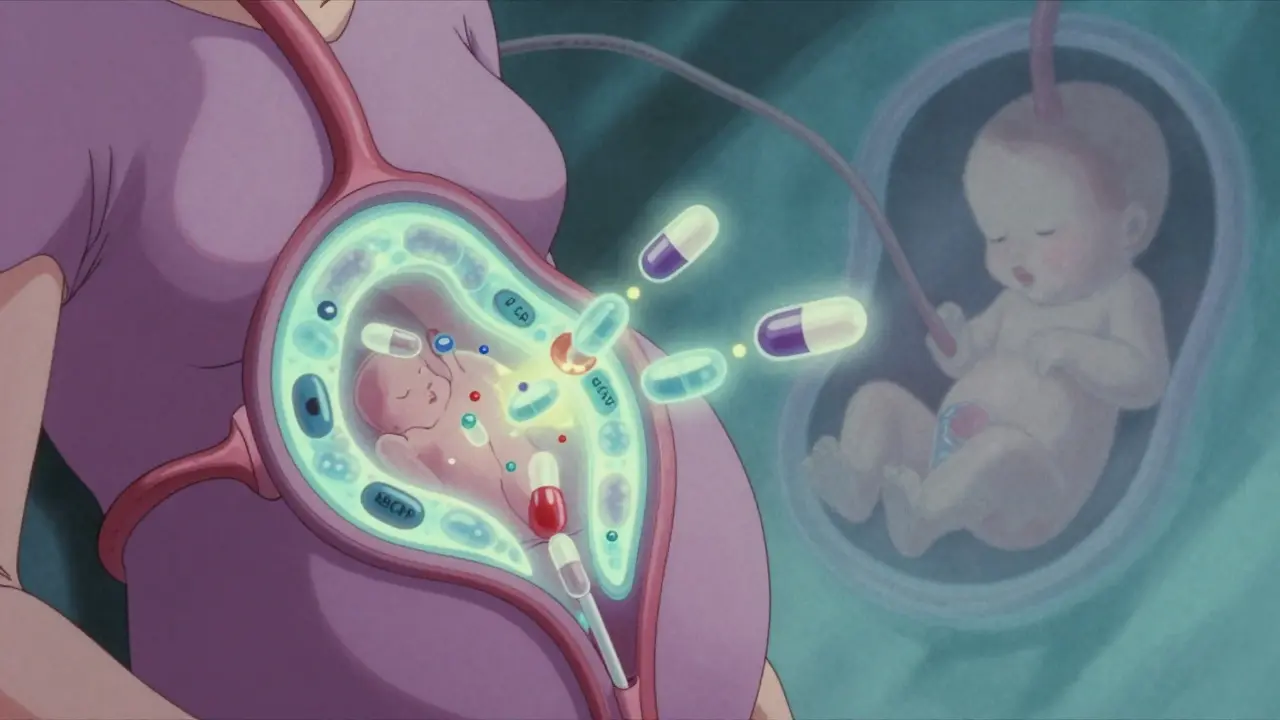

When a pregnant person takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in their body. It travels through the bloodstream, reaches the placenta, and can cross over to the developing fetus. This isn’t science fiction-it’s everyday biology. And while some drugs pass through easily, others barely make it. The difference can mean the difference between a healthy baby and serious complications.

The placenta isn’t a wall-it’s a gatekeeper

For decades, doctors thought the placenta acted like a shield, blocking harmful substances from reaching the baby. That idea was shattered in the late 1950s when thousands of babies were born with severe limb defects after their mothers took thalidomide for morning sickness. The drug didn’t just cross the placenta-it caused irreversible damage. Since then, we’ve learned the placenta isn’t a barrier. It’s a selective filter. At full term, the placenta weighs about half a kilogram, spans 15-20 centimeters across, and has a surface area the size of a small rug-nearly 15 square meters. That’s a lot of space for molecules to move back and forth. But not everything gets through. The placenta uses several mechanisms to decide what passes and what gets blocked.How drugs actually cross over

There are four main ways medications move from mother to fetus:- Passive diffusion-the most common route. Small, fat-soluble molecules slip through cell membranes easily. Think alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine. These cross quickly and often reach near-equal levels in mother and baby.

- Active transport-the placenta has special protein pumps that push certain drugs back into the mother’s blood. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) are two key players. They’re like bouncers at a club, kicking out unwanted guests.

- Facilitated diffusion-some drugs hitch a ride on transporters meant for nutrients. Zidovudine, an HIV drug, uses these to cross efficiently.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis-larger molecules like antibodies (IgG) are carried in vesicles. This is why some immunotherapies can reach the fetus.

Size matters. Drugs under 500 daltons (Da) cross much more easily. Insulin, at over 5,800 Da, barely gets through. But even small drugs can be blocked if they’re highly bound to proteins in the mother’s blood. Warfarin, for example, is 99% bound-so only 1% is free to cross. That’s why its fetal exposure is low, despite being small and fat-soluble.

What happens when drugs get through?

Once a drug reaches the fetus, its effects depend on two things: the stage of development and the drug’s pharmacology. In the first trimester, the placenta is more porous. Tight junctions between cells aren’t fully formed, and efflux pumps like P-gp aren’t working at full strength. That means drugs can enter more easily during the critical window of organ formation. A medication that’s safe later in pregnancy might be dangerous early on. Take SSRIs like sertraline. They cross the placenta with a cord-to-maternal ratio of 0.8 to 1.0-meaning the baby gets almost as much as the mother. About 30% of newborns exposed to these drugs show temporary symptoms like jitteriness, feeding trouble, or breathing issues. These usually resolve within days, but they’re still a sign the drug reached the baby. Opioids are even more concerning. Methadone reaches fetal levels at 65-75% of maternal concentration. That’s why 60-80% of babies born to mothers on methadone develop neonatal abstinence syndrome-withdrawal symptoms like crying, tremors, and seizures. The same goes for buprenorphine and morphine. These drugs don’t just cross-they stick around in fetal tissues longer than in adults. Antiepileptic drugs like valproic acid cross easily and are linked to a 10-11% risk of major birth defects-nearly five times higher than the general population. Phenobarbital, another seizure drug, reaches near-equal levels in the fetus. Even though it’s been used for decades, we’re still learning how it affects brain development.

Why some drugs barely make it

Not all drugs are created equal. HIV protease inhibitors like lopinavir and saquinavir are designed to fight viruses, but they’re also stubbornly blocked by placental pumps. In perfused placenta studies, inhibiting P-gp increased lopinavir transfer by 70%. Without that block, fetal levels would be much higher. That’s actually good news. For drugs that could harm the fetus, the placenta’s efflux systems act as a safety net. But this also means treating infections in pregnancy is harder. If a drug can’t reach the fetus, it can’t treat fetal infections. That’s why researchers are exploring ways to temporarily block these pumps-without risking toxicity. Chemotherapy drugs like paclitaxel cross at 25-30% efficiency. But when P-gp is inhibited, that jumps to 45-50%. That’s a double-edged sword: better treatment for the fetus, but higher risk of damage. Methotrexate, used for autoimmune conditions and some cancers, barely crosses because the placenta lacks the transporters it needs. That’s why it’s sometimes preferred in early pregnancy-but only under strict supervision.Research is catching up

For years, scientists relied on animal studies to predict how drugs affect human fetuses. But mouse and rat placentas are structurally different. They’re more permeable. A drug that seems safe in mice might be dangerous in humans. Now, researchers use dually perfused human placentas-live tissue from C-sections kept alive in the lab. These models show real-time drug transfer. One study found glyburide, a diabetes drug, crossed at just 5.6% efficiency, thanks to BCRP. That matched what was seen in actual human samples. Even more advanced are placenta-on-a-chip devices-microfluidic systems that mimic the placental barrier using human cells. These can test hundreds of compounds quickly and accurately. One 2022 version matched ex vivo data at 92% accuracy. The NIH’s Human Placenta Project has also developed non-invasive imaging using radioactive tracers to watch drugs move in real time. For the first time, we can see exactly where a drug goes inside the fetus-like whether it accumulates in the liver or brain.What this means for pregnant people

If you’re pregnant and taking medication, don’t stop abruptly. But do talk to your doctor. Many drugs are safe. Some aren’t. The key is knowing which ones. Ask:- Is this drug necessary?

- Is there a safer alternative?

- What’s the evidence for fetal safety?

The FDA now requires drug labels to include specific data on placental transfer and fetal risk. Look for the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (2015) updates. If a drug doesn’t have clear data, that’s a red flag.

Therapeutic drug monitoring is critical for drugs with narrow safety margins-like digoxin or lithium. Even if the placenta doesn’t block them, small changes in maternal dose can lead to big changes in fetal exposure.

And here’s something most people don’t realize: the placenta changes over time. What’s safe at 20 weeks might be riskier at 35 weeks. That’s why guidelines recommend reassessing medication use in each trimester.

Christina Bischof

15 December, 2025 04:07 AMThe placenta being a gatekeeper not a wall makes so much sense now

I always thought it was like a force field blocking everything

Turns out it’s just picky about who gets in

Melissa Taylor

15 December, 2025 19:46 PMThis is one of those topics that should be taught in high school biology

Most people have no idea how delicate this process is

And yet so many assume if it’s in the mom’s system, it’s automatically safe for the baby

It’s not magic, it’s biology-and it’s incredibly nuanced

Thank you for breaking this down without fearmongering

People need to understand that ‘safe’ isn’t binary

Some drugs cross easily, some don’t, and timing matters more than we think

That’s why blanket ‘no meds during pregnancy’ advice is dangerous

It’s not about avoiding all risk-it’s about managing it wisely

Every pregnant person deserves access to this kind of clarity

Not just those who can afford a specialist or spend hours reading journals

Knowledge should be free, not a privilege

And this post? It’s a gift

John Brown

16 December, 2025 19:44 PMI’ve seen too many moms panic and quit their antidepressants cold turkey

Then end up in the ER because their depression spiraled

And now the baby’s at risk from that too

It’s not about taking meds-it’s about taking the right ones

And knowing when to adjust

The placenta doesn’t care about your fears

It just follows the science

So do your research, talk to your OB, don’t guess

Jake Sinatra

18 December, 2025 02:50 AMIt’s fascinating how P-glycoprotein acts as a biological bouncer

Evolution didn’t design the placenta to be a perfect shield

It was designed to be selective-balancing nutrient delivery with toxin exclusion

Modern pharmacology is only now catching up to what nature built over millions of years

The fact that we can now model this with organ-on-a-chip technology is revolutionary

But we still lack longitudinal data on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes

That’s the next frontier

And it requires ethical, large-scale human studies

Which brings us back to the need for better labeling and transparency from pharma

RONALD Randolph

19 December, 2025 13:16 PMWhy are we even letting pregnant women take ANY drugs? It’s reckless.

Back in my day, we just suffered through nausea and didn’t poison our babies.

Now it’s all ‘safe meds’ and ‘personal choice’-until something goes wrong.

Then it’s the system’s fault.

Wake up.

The placenta isn’t a suggestion-it’s a warning.

Raj Kumar

19 December, 2025 15:34 PMBro this is wild

So like, if you got HIV and on meds, the placenta literally kicks out the drugs

But if you stop, baby gets HIV

So we gotta trick the placenta?

That’s like hacking your own body

Mad respect to the scientists

Also why is methotrexate not crossing? Is it because Indian food? Just asking

JK but seriously, this is life-saving info

Why isn’t this on every OB’s wall?

Michelle M

21 December, 2025 09:16 AMIt’s humbling to think that for nine months, your body is hosting a tiny, developing universe

And every molecule you ingest becomes part of its story

There’s no perfect answer, only careful choices

And the quiet courage it takes to make them

The placenta doesn’t judge

It just filters

But we? We carry the weight of every decision

That’s not science

That’s love in motion

Lisa Davies

21 December, 2025 22:52 PMOMG I just found out my anxiety med crosses easily 😳

But my doc said it’s safer than untreated anxiety

So I’m keeping it

And now I get why

Thanks for the clarity!! 🙏

John Samuel

23 December, 2025 02:26 AMThe elegance of the placental barrier is a masterpiece of evolutionary biochemistry

It operates not through brute force, but through molecular discernment

Efflux transporters like P-gp and BCRP are not mere gatekeepers-they are arbiters of life

And the emergence of placenta-on-a-chip models represents not merely technological advancement, but a paradigm shift in perinatal pharmacology

One must pause and reflect: we are now capable of observing, in real time, the transport of xenobiotics across a human-derived barrier

That is nothing short of miraculous

And yet, the ethical boundaries of intervention remain as complex as the biology itself

May we proceed with both rigor and reverence

Nupur Vimal

24 December, 2025 21:53 PMYou think you know what’s safe but you don’t

Everyone thinks their meds are fine

But the data is messy

And doctors don’t always know

So stop pretending you’re an expert

Just trust your doctor and shut up

Jocelyn Lachapelle

26 December, 2025 15:04 PMI’m from a culture where pregnancy means no medicine, no caffeine, no stress

But this post changed how I see it

It’s not about total avoidance

It’s about smart choices

My sister took sertraline and had a healthy baby

She didn’t suffer in silence

She asked questions

And now I’m telling everyone I know

Knowledge isn’t betrayal

It’s protection

Cassie Henriques

27 December, 2025 17:22 PMSo if P-gp is blocking HIV meds, does that mean fetal HIV exposure is lower than we thought?

But then why do we still see vertical transmission?

Is it because the drug concentration is subtherapeutic in the fetus?

Or are we missing other transporters?

And what about placental inflammation from maternal infection-does that alter permeability?

This is why we need more human placental perfusion studies

Not just in the US but globally

Because drug transport isn’t uniform across ethnicities

Genetics matter

And we’re still treating pregnancy like a one-size-fits-all experiment

Sai Nguyen

29 December, 2025 14:47 PMAmericans think they can drug their way through everything.

Even pregnancy.

It’s not science.

It’s arrogance.

Mike Nordby

30 December, 2025 07:15 AMThank you for the comprehensive and meticulously referenced overview.

This level of detail is precisely what is missing from public health messaging.

The distinction between passive diffusion and receptor-mediated endocytosis is not merely academic-it directly informs clinical decision-making.

Furthermore, the emphasis on trimester-specific placental permeability is critical.

I would only add that future guidelines should integrate pharmacogenomic data, particularly regarding polymorphisms in ABC transporters, which vary significantly across populations.

This is not a one-size-fits-all biological system.

And until we acknowledge that, we risk both under- and over-treatment.

Well done.