When you walk into a pharmacy and pick up a generic version of your blood pressure pill, you might assume more competitors means lower prices. It makes sense - more companies making the same drug should drive costs down, right? But in the real world of pharmaceutical markets, that’s not always what happens. Even when five or six generic versions of a drug are on the shelf, prices don’t always drop as expected. Sometimes they barely move at all.

More Competitors, But Not Always Lower Prices

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found that when a single generic enters the market, prices for brand-name drugs drop by 30% to 39%. With two generics, that jump to 54%. By the time six or more companies are selling the same drug, average manufacturer prices can fall by 95%. Sounds great - until you look closer.

In Portugal, regulators set price caps on statins, drugs used to lower cholesterol. Even with multiple generic manufacturers approved, prices stayed stubbornly close to those caps. Why? Because the companies weren’t fighting each other - they were quietly coordinating. When the same few players compete across dozens of drug markets, they learn not to undercut each other. It’s called mutual forbearance. They know if one cuts prices, the others will follow, and everyone loses. So they don’t cut at all.

This isn’t just Europe. In China, researchers studied 27 brand-name drugs after generics entered the market. Eight quarters later, 15 of those brand drugs still held over 70% of the market. And in 70% of cases, there were only one or two generic competitors - far fewer than the system allowed. Some brand companies didn’t even lower their prices. A few actually raised them by 0.62% on average. Why? Because patients and doctors still trusted the original brand. If you believe your heart medication from the big-name company is safer, you’re less likely to switch, even if the generic costs half as much.

The Hidden Barriers to Real Competition

Not all generic drugs are created equal. Simple pills - like metformin for diabetes - are easy to copy. But complex drugs? Those are a different story.

Drugs with special delivery systems - like extended-release capsules, inhalers, or injectables with precise dosing - require manufacturers to prove they’re identical in every way: how the drug dissolves, how it’s absorbed, even how it behaves in the body over time. This isn’t just a lab test. It’s a multi-year, multi-million-dollar process called Q1-Q3 bioequivalence testing. Only the biggest generic companies can afford it. That means even if 10 companies get approval, only two or three actually make the drug. The rest? They sit on their paperwork.

DrugPatentWatch found that innovators use this to their advantage. They file dozens of patents - not just on the active ingredient, but on packaging, coatings, manufacturing methods. Generic makers have to fight through this legal maze. Some settle for cash payments to delay entry. These “pay-for-delay” deals, though now restricted, still happen. And when they do, they keep prices high for years.

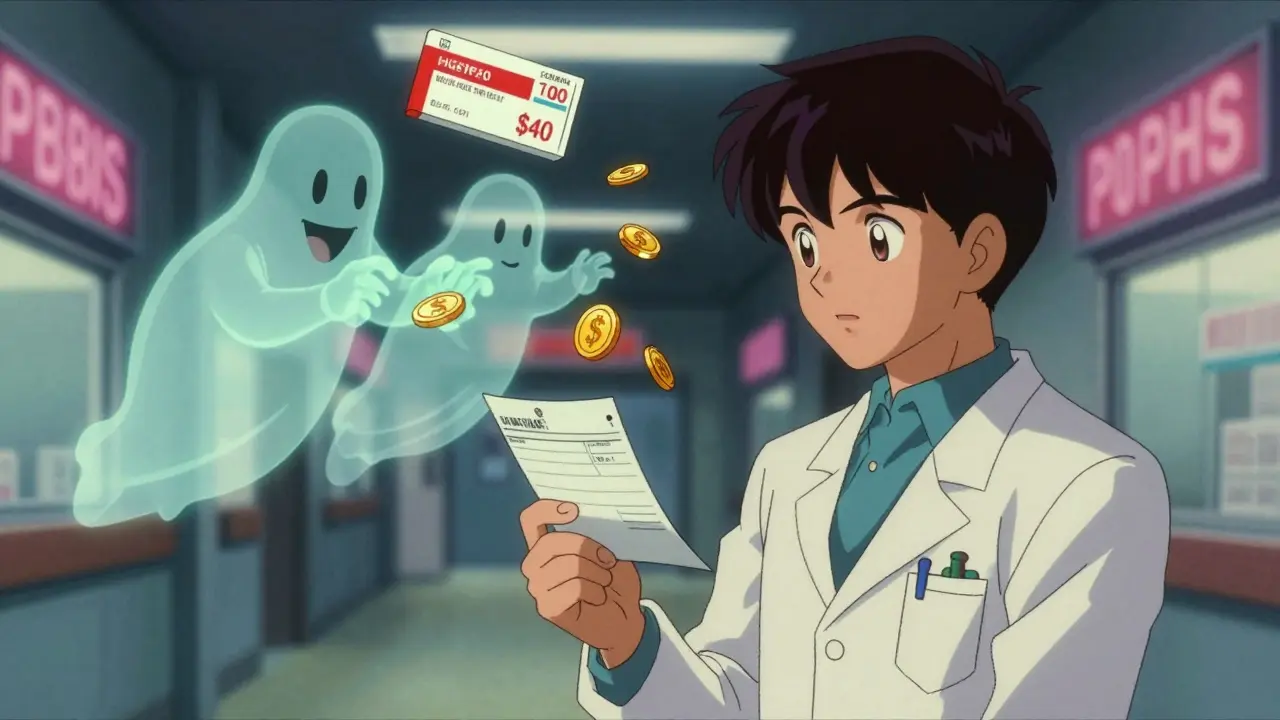

Who Really Controls the Market?

It’s not just the drugmakers. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) - the middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drug companies - control 90% of drug purchases in the U.S. Their job is to negotiate discounts. But they don’t always pass savings to patients. Instead, they create rebate systems that reward higher list prices. A drug might cost $100 at the pharmacy counter, but the PBM gets a $40 rebate from the maker. So even if generics are cheaper, PBMs may push the more expensive brand if the rebate is bigger.

Then there are authorized generics - the brand company’s own generic version, sold during the first six months of exclusivity. If the brand owns it, they lower their own wholesale price by 8-12%. But if a different company makes the authorized generic, the original brand raises its price by 22%. Why? Because they’re not competing with themselves - they’re competing with someone else. And they know the market will pay more.

Why Some Markets Stay Stuck

Regulation shapes competition more than most people realize. In countries with centralized pricing - like the UK or Canada - the government sets one price for all versions of a drug. No matter how many generics enter, the price doesn’t drop further. In the U.S., where prices are negotiated privately, competition *can* drive prices down - but only if the market structure allows it.

Take the first generic to enter the U.S. market. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, that company gets 180 days of exclusivity. During that time, they capture about 80% of the market. That’s a huge reward. But it also scares off others. Why spend millions to enter if you’ll only get 10% of the pie? So many stay out. The result? Even when a drug has multiple approvals, only one or two are actually sold.

That’s why the average number of generic competitors per drug eight quarters after entry is just 2.4. Only 29.6% of drugs have three or more. That’s not competition - that’s a monopoly with a few small players.

The Supply Chain Advantage

But here’s the twist: when multiple companies *do* make the same drug, the system becomes more stable. Between 2018 and 2022, drugs with three or more manufacturers had 67% fewer shortages than single-source generics. Why? Because if one factory shuts down - due to FDA violations, natural disaster, or supply chain issues - another can pick up the slack.

That’s not just about price. It’s about access. When patients rely on a drug every day - like insulin, thyroid medication, or seizure control - a shortage can be life-threatening. Multiple competitors aren’t just good for lowering costs. They’re critical for keeping drugs on the shelf.

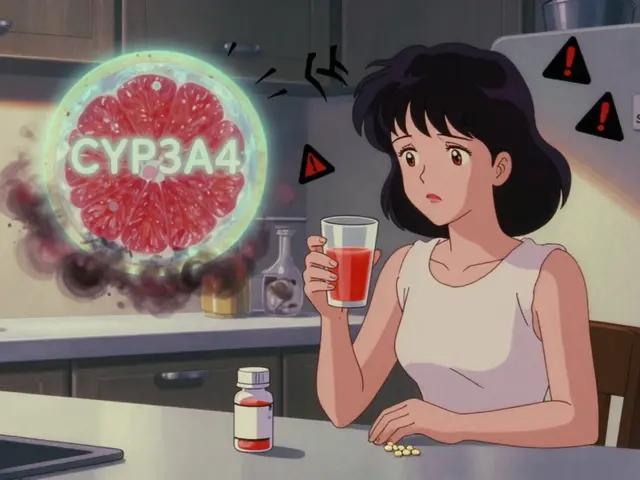

The New Threat: Medicare Price Negotiation

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for 10 high-cost brand drugs each year. By 2025, that number will grow. The goal is to lower costs. But there’s a hidden risk.

Generic manufacturers enter markets because they can make money. If Medicare caps the price of a brand drug at $50 a month, and the generic costs $40 to make, there’s no profit left. Why would a generic company invest millions to get approval if they can’t sell it for more than $50? They won’t.

Lumanity’s 2023 analysis warns this could shrink generic competition in therapeutic areas where Medicare negotiates prices. We might end up with fewer generics, not more. And without competition, even the lowest negotiated price could become the new high.

What’s Next for Generic Drugs?

Big pharma is shifting focus from small-molecule pills to complex biologics - drugs made from living cells, like insulin or cancer treatments. These are harder to copy. The first biosimilars are coming, but they cost $100 million to develop, not $5 million. And they don’t cut prices by 85% like small-molecule generics do. More like 15-30%.

That means the old model - many cheap generics driving down prices - won’t work for the next generation of medicines. We’ll need new rules. Maybe value-based pricing. Maybe government-backed manufacturing. Or maybe, we’ll just pay more.

The lesson? More generic competitors don’t automatically mean lower prices. It depends on who’s making the drug, who’s buying it, how complex it is, and what rules are in place. Real competition isn’t about approvals on paper. It’s about who’s actually selling, and why.

Glendon Cone

1 January, 2026 08:28 AMMan, I never realized how much of a mess this system is. I just grab my metformin like it’s candy, never thinking about who made it or why it costs $5 instead of $0.50. Turns out it’s not about supply-it’s about who’s holding the leash. 😅

kelly tracy

2 January, 2026 06:35 AMThis is why capitalism is a lie. Everyone pretends competition lowers prices but the real winners are the ones who control the rules. PBMs, patent trolls, and pharma CEOs are laughing all the way to the bank while you choose between food and insulin.

srishti Jain

2 January, 2026 10:53 AMSame. My thyroid med went up 40% last year. No new brands. No new generics. Just more corporate greed.

Cheyenne Sims

3 January, 2026 20:02 PMThe structural inefficiencies described herein are not merely market anomalies-they are systemic failures of regulatory architecture. The absence of transparent pricing mechanisms and the proliferation of patent thickets constitute a violation of antitrust principles under the Sherman Act. This is not capitalism-it is rent-seeking masquerading as innovation.

Shae Chapman

4 January, 2026 16:37 PMI just cried reading this. My mom’s heart meds were unavailable for 3 months last year. We had to drive 90 miles to find a pharmacy that had stock. It’s not just about money-it’s about people’s lives. 🥺 We need real change, not more paperwork.

Kelly Gerrard

5 January, 2026 12:38 PMMore generics dont mean lower prices because the system is rigged. End of story. Stop pretending this is about free markets. Its about control.

Henry Ward

7 January, 2026 11:18 AMYou people act like this is a surprise. Big Pharma has been running this scam since the 80s. They don't care if you die-they care if their quarterly earnings look good. Wake up.

Nadia Spira

8 January, 2026 03:50 AMThe hegemonic structure of pharmaceutical capital is predicated on the commodification of biological necessity. The fetishization of patent exclusivity functions as a disciplinary mechanism, rendering the body as a site of rent extraction. The PBM complex, as a necropolitical intermediary, mediates life and death through rebate arbitrage.

henry mateo

9 January, 2026 00:52 AMso like… if one factory shuts down and no one else makes the drug… people just… dont get it? thats wild. i had no idea. my grandpa died because his blood pressure med ran out and they couldnt find another. this is insane.

Kunal Karakoti

9 January, 2026 08:11 AMIt’s fascinating how we equate quantity with competition, but real competition requires incentive alignment. When the players are incentivized to avoid price wars rather than engage in them, we get the illusion of choice without the reality of savings. The market isn’t broken-it’s designed this way.

Aayush Khandelwal

10 January, 2026 12:54 PMThink of it like a poker table where everyone knows the other players’ hands. No one goes all-in because they know the pot will collapse. That’s mutual forbearance. The FDA approves 6 generics, but only 2 play the game. The rest are just sitting on the bench, waiting for the next round. And the house always wins.

Sandeep Mishra

12 January, 2026 12:50 PMHey everyone-this is why we need public manufacturing. Not just for generics, but for essential meds. Imagine if the government made insulin like it makes vaccines. No profit motive. No patent games. Just supply. I know it sounds radical, but when people die because a company won’t lower the price… what’s more radical? That, or fixing it?

Also, shoutout to the folks who make these drugs in clean rooms every day. They’re the real heroes.

Joseph Corry

13 January, 2026 08:25 AMHow is it possible that a society that prides itself on innovation can’t solve a problem this basic? We landed on the moon, but we can’t ensure a diabetic gets their insulin? This isn’t economics-it’s moral bankruptcy dressed in a suit.