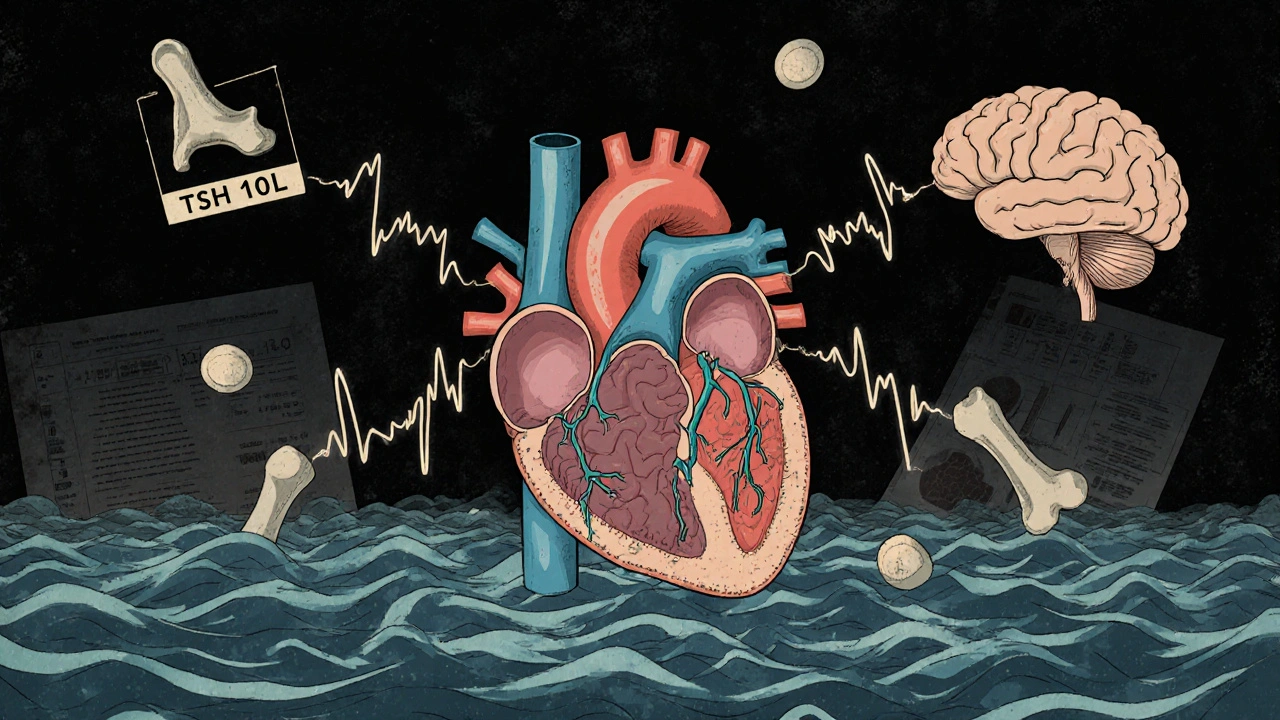

Most people don’t realize their thyroid is quietly affecting their heart - until something goes wrong. Subclinical hyperthyroidism is one of those silent conditions. Your thyroid hormone levels look normal on blood tests, but your TSH - the brain’s signal to the thyroid - is too low. It’s not overt hyperthyroidism with shaking hands or rapid weight loss. It’s subtler. And for older adults, especially those over 65, it can quietly raise the risk of heart problems you might never see coming.

What Exactly Is Subclinical Hyperthyroidism?

Subclinical hyperthyroidism means your thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is below 0.45 mIU/L, but your free T4 and free T3 - the actual thyroid hormones - stay within the normal range. That’s the technical definition. In real life, it often shows up during a routine check-up. Someone gets their cholesterol checked, or their doctor orders blood work for fatigue, and suddenly there’s a low TSH. No symptoms. No obvious reason. Just a number that doesn’t fit.

This isn’t rare. About 4 to 8% of the general population has it. But the numbers climb sharply with age. In people over 75, up to 15.4% show signs of subclinical hyperthyroidism. The most common causes? Toxic nodular goiter - one or more overactive lumps in the thyroid - or too much thyroid medication in people being treated for hypothyroidism. It’s not always the thyroid’s fault. Sometimes, it’s the treatment.

Why the Heart Is the Biggest Concern

The thyroid doesn’t just control metabolism. It talks directly to your heart. Even when hormone levels are normal, a suppressed TSH sends signals that make your heart work harder. Studies show clear links between low TSH and three major heart risks: atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and structural changes in the heart muscle.

One major analysis of over 8,700 people found that those with TSH below 0.1 mIU/L had more than double the risk of developing atrial fibrillation - an irregular, often rapid heart rhythm that can lead to stroke. Even those with TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L had a 63% higher risk. For someone over 60, that’s not a small bump. That’s a red flag.

Heart failure risk also rises. A 10-year study of nearly 25,400 people showed those with TSH under 0.1 had almost double the chance of heart failure compared to people with normal thyroid function. Another study of 71 patients found the risk was nearly three times higher. And it wasn’t just about rhythm. The heart’s left ventricle thickens, the muscle doesn’t relax properly between beats, and heart rate variability drops - meaning the nervous system’s control over the heart gets weaker. All of this happens without the person feeling any different.

These changes aren’t theoretical. They show up on echocardiograms and EKGs. And once they start, they don’t always reverse - even if TSH later normalizes.

Other Risks: Bones, Brain, and Quality of Life

The heart isn’t the only system at risk. Subclinical hyperthyroidism also weakens bones. People with TSH below 0.1 mIU/L have a 2.3 times higher risk of fractures, especially hip and spine fractures in older adults. The reason? Thyroid hormones speed up bone turnover. Without enough TSH to slow things down, bone density drops faster than it should.

Cognitive effects are less clear, but emerging data suggests subtle changes. A 2016 study in older adults found declines in executive function - things like planning, focus, and decision-making - in those with persistent low TSH. It’s not dementia. But it’s enough to make daily tasks feel harder.

Quality of life? Most people feel fine. That’s why it’s so easy to ignore. But if you’re already dealing with heart disease, osteoporosis, or memory issues, even mild thyroid overactivity can make things worse. It’s not the cause, but it’s a contributor.

When Should You Treat It?

This is where things get complicated. Not everyone with low TSH needs treatment. But not everyone should be left alone, either. Guidelines agree on one thing: the lower the TSH, the higher the risk.

If your TSH is below 0.1 mIU/L - especially if you’re over 65, have heart disease, high blood pressure, or osteoporosis - treatment is usually recommended. The goal isn’t to chase a perfect number. It’s to prevent heart rhythm problems, bone breaks, and long-term damage. Options include radioactive iodine to reduce thyroid activity, surgery to remove overactive nodules, or adjusting thyroid medication if you’re on levothyroxine.

If your TSH is between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L - and you’re otherwise healthy - most doctors will watch and wait. But not if you have symptoms: palpitations, unexplained weight loss, trouble sleeping, or worsening heart disease. Then treatment becomes reasonable. Beta-blockers like metoprolol are often used first. They don’t fix the thyroid, but they calm the heart. They lower heart rate, reduce palpitations, and can help reverse some of the thickening in the heart muscle.

The biggest mistake? Treating too aggressively. If you lower TSH too much - pushing it into the hypothyroid range - you trade one problem for another. Hypothyroidism also raises heart disease risk, especially in older adults. It’s a balancing act.

Who Makes the Call?

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule. That’s why experts stress individualized decisions. Dr. Jacqueline Jonklaas, who helped write the American Thyroid Association guidelines, says treatment should be based on clinical judgment - not just numbers. If you’re 72 with atrial fibrillation and a TSH of 0.08, treating it makes sense. If you’re 68, active, no heart issues, and your TSH is 0.35? Maybe just monitor it every six months.

European guidelines are stricter. They recommend treating all cases with TSH below 0.1, regardless of symptoms. American guidelines are more cautious. The difference? Cultural approach, not science. Both sides agree on the risks. They just disagree on when to act.

Monitoring: What to Do While You Wait

If you’re not treating right away, you still need to keep tabs. Here’s what most doctors recommend:

- TSH below 0.1 mIU/L: Check every 3 to 6 months. Watch for rising heart rate, new palpitations, or bone density changes.

- TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L: Annual checks are fine if you’re healthy and symptom-free.

- Always get an EKG and echocardiogram: Especially if you’re over 60. These tests catch heart changes before you feel them.

- Check bone density: Especially if you’re postmenopausal or have a history of fractures.

Don’t wait for symptoms. By the time you feel something, the damage may already be there.

What’s Next? Research on the Horizon

Doctors still don’t have perfect answers. That’s why major studies are underway. The THAMES trial at UCLA is tracking people with TSH below 0.1 to see if treating them early prevents heart events. The DEPOSIT study across 15 European centers is following 5,000 older adults with subclinical hyperthyroidism to find out what truly affects long-term survival.

The American Heart Association has called for more randomized trials. Right now, most evidence comes from observational studies. We know there’s a link. But we need proof that treating improves outcomes - not just changes numbers.

Until then, the best approach is simple: know your TSH. Know your heart. Know your bones. And don’t ignore a low TSH just because you feel fine. Your heart doesn’t care how you feel. It only cares what your numbers say.

Can subclinical hyperthyroidism cause atrial fibrillation?

Yes. Multiple large studies show a clear link. People with TSH below 0.1 mIU/L have more than double the risk of developing atrial fibrillation compared to those with normal thyroid function. Even those with TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L have a 60% higher risk. This is especially true in people over 60.

Do I need treatment if I feel fine?

It depends. If your TSH is below 0.1 mIU/L and you’re over 65, have heart disease, or osteoporosis, treatment is usually recommended - even without symptoms. If your TSH is between 0.1 and 0.44 and you’re otherwise healthy, monitoring is often enough. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your heart is safe.

Can thyroid medication cause subclinical hyperthyroidism?

Yes. Taking too much levothyroxine for hypothyroidism is one of the most common causes. Many older adults are on thyroid replacement and accidentally end up with a suppressed TSH because their dose hasn’t been adjusted as their body changed with age. Regular TSH checks are critical if you’re on thyroid medication.

What are the treatment options?

Treatment depends on the cause. If it’s from too much medication, lowering the dose usually fixes it. If it’s from a toxic nodule, options include radioactive iodine (to destroy overactive tissue), surgery (to remove the nodule), or beta-blockers to manage heart symptoms. Beta-blockers don’t cure the thyroid issue, but they help protect the heart while you decide on next steps.

How often should I get my TSH checked?

If your TSH is below 0.1 mIU/L, check every 3 to 6 months. If it’s between 0.1 and 0.44 and you have no risk factors, once a year is usually enough. If you have heart disease, osteoporosis, or are over 65, your doctor may recommend more frequent checks - even if your TSH is in the milder range.

Is subclinical hyperthyroidism dangerous for younger people?

Less so. In people under 60 without heart disease or bone loss, the risks are much lower. Many experts don’t treat mild cases in younger adults unless symptoms appear. But if you’re young and have a very low TSH (below 0.1) and a toxic nodule, treatment may still be needed to prevent progression to overt hyperthyroidism.

jamie sigler

27 November, 2025 23:20 PMUgh, another doctor post pretending they know what’s best. I’ve had a low TSH for years and I feel fine. Why should I take some radioactive junk or tweak my meds just because some lab number is ‘off’? My heart’s fine, my bones are fine, I’m not falling apart. Stop scaring people over numbers.

Bernie Terrien

29 November, 2025 11:46 AMLow TSH? More like low *common sense*. They’re turning a biomarker into a death sentence. Atrial fibrillation? Sure - but correlation isn’t causation. You could just as easily blame bad coffee, sleep apnea, or the fact that people over 65 are basically walking time bombs. The real villain? Overmedication culture. And the docs who treat labs like oracle bones.

Jennifer Wang

29 November, 2025 19:03 PMIt is imperative to recognize that subclinical hyperthyroidism, particularly in the elderly population, constitutes a clinically significant condition associated with measurable increases in cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality. The evidence base, derived from large longitudinal cohorts including the Framingham Heart Study and the Rotterdam Study, demonstrates unequivocally that TSH levels below 0.1 mIU/L are independently predictive of atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, and reduced bone mineral density. Intervention, when indicated, is not speculative - it is evidence-based preventive medicine. Monitoring should include quarterly TSH, annual ECG, and baseline dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in high-risk individuals. Delaying intervention until symptomatology emerges may preclude full reversibility of cardiac remodeling.

stephen idiado

1 December, 2025 14:22 PMSubclinical hyperthyroidism is a pharma construct. TSH is a surrogate marker - not a physiological parameter. The thyroid is an adaptive organ. Suppressing TSH isn’t pathology - it’s homeostasis under metabolic stress. You’re treating a shadow, not a disease. And the heart risks? Confounded by age, statins, and chronic inflammation. This is medicalization disguised as science.

Subhash Singh

2 December, 2025 01:29 AMGiven the robust epidemiological data linking suppressed TSH to adverse cardiac outcomes, particularly in individuals over the age of 65, it is reasonable to question whether current guidelines are sufficiently proactive. While observational studies demonstrate association, the absence of randomized controlled trials raises legitimate methodological concerns. Nevertheless, the biological plausibility - mediated via direct thyrocyte-cardiac receptor interactions and sympathetic overdrive - warrants a cautious, individualized approach. I would advocate for early echocardiographic screening in all patients with persistent TSH < 0.4 mIU/L, irrespective of symptoms.

Geoff Heredia

2 December, 2025 23:18 PMThey don’t want you to know this, but the FDA and Big Pharma are pushing this ‘subclinical’ nonsense to sell more beta-blockers and radioactive iodine. Why? Because treating ‘normal’ people is way more profitable than fixing the real problem: environmental toxins, mold exposure, and glyphosate poisoning your thyroid. Look up the thyroid industry’s lobbying numbers. They’re spending billions to turn every low TSH into a ‘condition.’ You’re being monetized. Check your water. Check your supplements. Stop trusting the lab report.

Tina Dinh

3 December, 2025 10:58 AMOMG YES. 😭 My grandma had this and no one caught it until she had a stroke. Please, if you’re over 60, get your TSH checked! 🫀🩺🦴 It’s not scary - it’s just smart. Don’t wait until your heart’s like a broken washing machine. 💪❤️ #ThyroidAwareness