Imagine waking up one day and realizing you can’t walk the way you used to. Your steps feel stuck, like your feet are glued to the floor. You forget names you knew for decades. You start having accidents you never had before. You tell yourself it’s just getting older. But what if it’s not aging? What if it’s something treatable? That’s the reality for many people with normal pressure hydrocephalus - a condition that mimics dementia but can often be reversed with a simple surgery.

What Is Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus?

Normal pressure hydrocephalus, or NPH, happens when too much cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up in the brain’s ventricles. Unlike other types of hydrocephalus, the pressure doesn’t spike. It stays in the normal range - between 70 and 245 mm H₂O - which is why it’s called "normal pressure." But even though the pressure is normal, the fluid overload stretches the brain tissue, especially around areas that control walking, thinking, and bladder control. It was first clearly described in 1965 by two neurosurgeons, Salomón Hakim and Raymond Adams. Since then, we’ve learned it mostly affects people over 60. About 0.4% of people over 65 have it. In nursing homes, that number jumps to nearly 6%. And here’s the kicker: up to 60% of these cases are misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. That means thousands of people are living with a condition that could be fixed - but no one’s checking for it.The Three Signs: Gait, Cognition, and Bladder Control

NPH doesn’t hit you with one symptom. It hits you with three - and they come in a very specific order. First, gait trouble. This isn’t just being a little slower. People with NPH develop what doctors call a "magnetic gait." Their feet shuffle, they take short steps, and they seem stuck in place. They might struggle to turn around or step over a curb. In studies, nearly 100% of diagnosed NPH patients have this symptom. It’s often the earliest and most obvious sign. Second, cognitive changes. This isn’t memory loss like Alzheimer’s. It’s slower thinking, trouble focusing, forgetfulness about appointments, and losing track of conversations. Neuropsychological tests show deficits in executive function - things like planning, organizing, switching tasks. The brain’s frontal lobes get compressed by the swollen ventricles, and that’s what messes with thinking. About 73% of NPH patients show clear cognitive decline. Third, urinary incontinence. This shows up later, and only in about one-third of cases. But when it does, it’s a red flag. You might not need all three symptoms to have NPH - only 29% of patients have the full triad. But if you have gait trouble plus any one of the other two, you should get checked.How Is It Diagnosed?

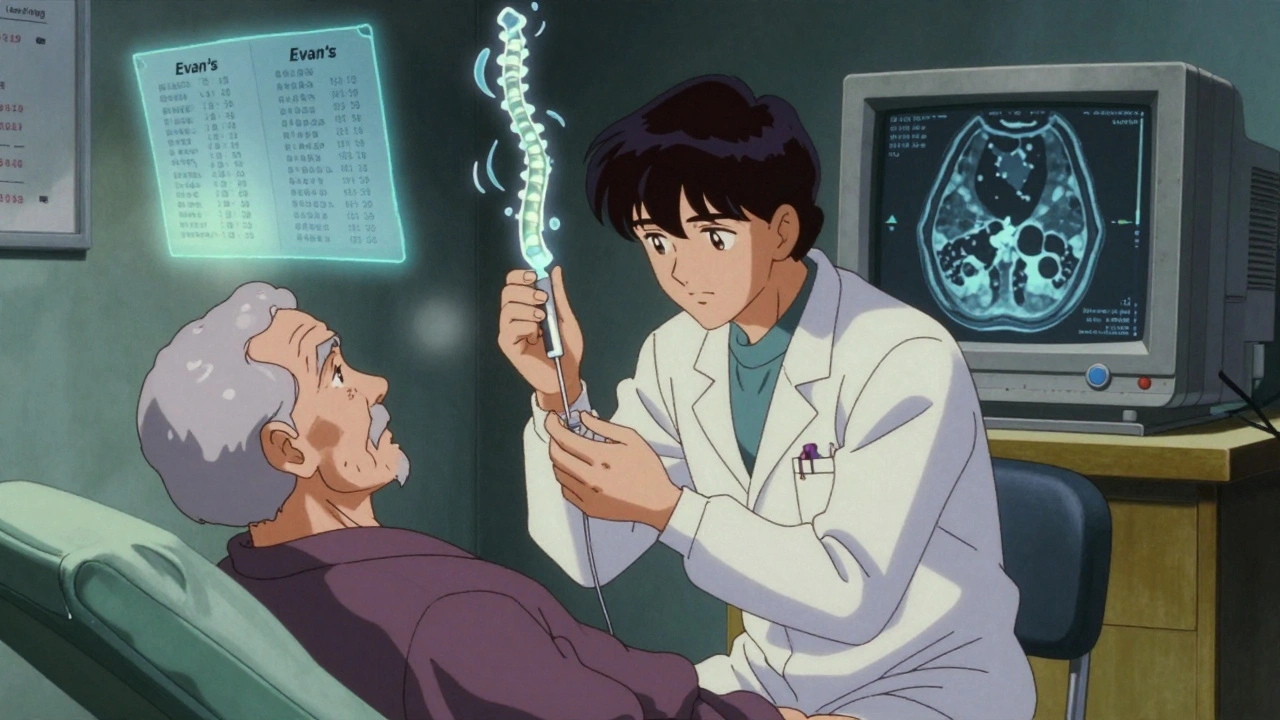

Most doctors don’t test for NPH unless they’re specialists. That’s why it takes, on average, 14 months from when symptoms start to when someone gets the right diagnosis. The first step is imaging. A CT scan or MRI will show enlarged ventricles. The key measurement is Evan’s index - if it’s 0.3 or higher, that’s a sign of ventriculomegaly. MRI can also spot periventricular edema - fluid leaking into brain tissue around the ventricles - which is a strong clue. Next comes the CSF tap test. This is simple: a doctor removes 30 to 50 milliliters of spinal fluid with a needle, like a lumbar puncture. Then they measure your walking speed, balance, and thinking ability before and after. If you improve by at least 10% on a timed 10-meter walk or a cognitive test, your chances of responding to a shunt jump to 82%. If you improve by 15% or more, your odds of success are nearly 9 in 10. Some centers use external lumbar drainage - a catheter left in place for a few days to drain fluid continuously. This gives a better sense of long-term improvement. But the tap test is faster, cheaper, and just as predictive in most cases.Shunt Surgery: The Only Treatment

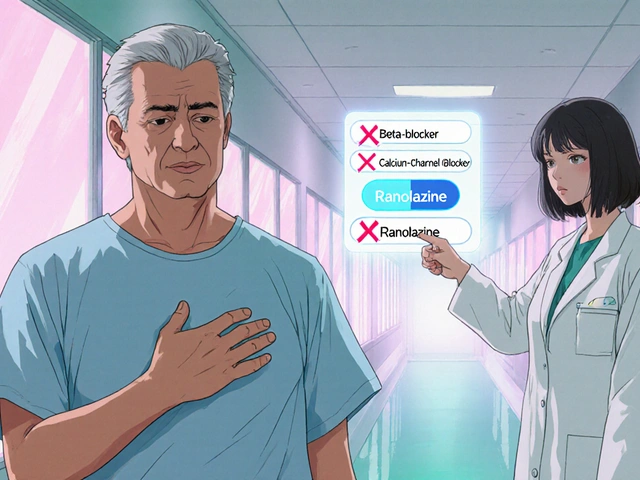

There’s no pill for NPH. No drug slows it down. The only proven treatment is surgery - a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt. Here’s how it works: Two thin tubes are placed. One goes into a ventricle in the brain. The other goes down to the abdomen. They’re connected by a valve that lets excess CSF drain slowly into the belly, where the body absorbs it. The valve is set to open at a pressure between 50 and 200 mm H₂O, depending on the patient. The surgery takes about an hour under general anesthesia. Most people go home in 2 to 3 days. Recovery takes 6 to 12 weeks. But the results? They can be dramatic. One 72-year-old man, after his shunt, cut his 10-meter walk time from 28 seconds to 12 seconds - in under two days. He started walking without help again. He regained bladder control after 18 months of accidents. Studies show 70 to 90% of properly selected patients improve after shunting. Gait improves in 76%, cognition in 62%, and continence in 58% within a year. Most people say their quality of life shoots up - and they’re glad they had the surgery.

Why Do Some Shunts Fail?

Not everyone gets better. About 20 to 30% of shunt surgeries don’t help. Why? One reason: misdiagnosis. If someone has Alzheimer’s mixed with NPH - which happens in 25 to 30% of cases - the shunt won’t fix the Alzheimer’s part. Another reason: the shunt doesn’t work right. It can get blocked, infected, or overdrain. About 15% of shunts fail within two years. Infection happens in 8.5% of cases. Subdural hematomas - bleeding on the brain - occur in 5.7%. Older patients, especially over 80, have higher infection rates. That’s why careful patient selection matters. If your tap test shows no improvement, don’t get the shunt. If you’ve had symptoms for over a year, your chances drop by 30%. Time matters.Different From Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s

It’s easy to confuse NPH with other brain disorders. But the differences are clear. Alzheimer’s starts with memory loss - forgetting names, repeating questions. Gait problems come much later, if at all. NPH starts with walking. You can still remember your grandchildren’s names, but you can’t get to the bathroom in time. Parkinson’s has tremors, stiffness, and slow movement - but not the magnetic gait. Parkinson’s patients often lean forward. NPH patients shuffle with feet flat on the ground, wide-based, like they’re walking on ice. Vascular dementia comes after strokes - symptoms jump in steps. NPH creeps in slowly, over months. MRI can tell them apart. NPH shows enlarged ventricles with periventricular edema. Alzheimer’s shows shrinking of the hippocampus. Parkinson’s looks normal on MRI until late stages.Barriers to Diagnosis and Care

Even though NPH is treatable, it’s underdiagnosed. Why? Doctors don’t think of it. Families assume it’s aging. Insurance won’t cover the tests. A 2022 survey found 37% of CSF tap tests were denied prior authorization. Medicare covers shunts - but not always the diagnostic steps. There’s also a lack of expertise. Interpreting CSF dynamics requires training. Few neurologists or neurosurgeons get that. The Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network says you need over 200 hours of specialized training to do it right. And then there’s the stigma. People don’t want to admit they’re losing control. They hide the accidents. They avoid walking. They stop going out. By the time they see a doctor, it’s too late for the best results.

What’s New in NPH Research?

There’s hope on the horizon. In 2022, the FDA approved a device called the Radionics CSF Dynamics Analyzer. It measures how well the brain drains CSF - giving a clearer picture than just pressure readings. It’s improving diagnostic accuracy to 89%. A new app, the iNPH Diagnostic Calculator, uses 12 clinical factors to predict shunt success with 85% accuracy. It’s being used in clinics from Boston to Berlin. And researchers are working on blood tests. Three Phase II trials are testing CSF protein markers that could one day diagnose NPH without a spinal tap. Preliminary results show 92% sensitivity. The Alzheimer’s Association and Hydrocephalus Association teamed up in 2023 to create new guidelines for patients with mixed dementia. The goal? Don’t miss NPH when it’s hiding in plain sight.What Should You Do?

If you or someone you love is over 60 and showing signs of slow walking, memory lapses, or bladder issues - don’t assume it’s normal aging. Talk to your doctor. Ask: "Could this be normal pressure hydrocephalus?" Request an MRI or CT scan. Ask for a CSF tap test if imaging shows enlarged ventricles. If your doctor says no, get a second opinion - from a neurologist who specializes in movement disorders or dementia, or a neurosurgeon who treats hydrocephalus. The window for treatment is narrow. But it’s not closed. And the payoff? It’s not just walking again. It’s going back to the kitchen, the garden, the church, the grandkids. It’s dignity.Long-Term Outlook

Shunts aren’t perfect. Most need at least one revision in their lifetime. The average shunt lasts 6.3 years. But even with revisions, long-term outcomes are good. A 20-year study in Sweden showed 68% of patients kept their improvements. The key is early action. The sooner you test and treat, the better the result. Delay past 12 months, and you lose 30% of your chance at full recovery. And while shunts aren’t risk-free, the risks of doing nothing are higher. Untreated NPH leads to falls, fractures, institutionalization, and complete dependence. Many patients end up in nursing homes - not because they’re too old, but because no one looked closely enough. NPH is not rare. It’s not untreatable. It’s just hidden.Can normal pressure hydrocephalus be cured?

NPH can’t be "cured" in the sense that the brain returns to its original state. But the symptoms - walking problems, memory issues, bladder control - can be reversed in 70-90% of patients with timely shunt surgery. Many regain independence and return to daily activities they thought were lost forever.

How do you test for normal pressure hydrocephalus?

Testing starts with an MRI or CT scan to check for enlarged brain ventricles. If those are abnormal, the next step is a CSF tap test: removing 30-50 mL of spinal fluid with a needle and measuring walking speed and mental function before and after. Improvement of 10% or more predicts shunt success with high accuracy. Some centers use external lumbar drainage for longer-term testing.

Is NPH the same as Alzheimer’s?

No. Alzheimer’s starts with memory loss and language problems, while NPH starts with walking difficulties. Alzheimer’s doesn’t improve with shunts. NPH does. MRI scans can help tell them apart - NPH shows enlarged ventricles and fluid around them, while Alzheimer’s shows shrinkage in memory areas of the brain. About 25-30% of NPH patients also have Alzheimer’s, making diagnosis harder.

What are the risks of shunt surgery?

Shunt surgery is generally safe, but risks include infection (8.5% of cases), shunt blockage (15.3% within two years), bleeding on the brain (5.7%), and overdrainage causing headaches. Older patients, especially over 80, have higher infection rates. Shunts may need revision over time - the average lasts about 6.3 years before needing adjustment or replacement.

How long does recovery take after a shunt?

Most patients go home within 2 to 3 days. Many see walking improvement within 48 hours. Full recovery - regaining strength, balance, and cognitive clarity - usually takes 6 to 12 weeks. Follow-up visits are needed at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months to check shunt function and adjust pressure settings if needed.

Can NPH come back after surgery?

The underlying condition doesn’t "come back," but the shunt can fail - it can get blocked, infected, or stop draining properly. Symptoms may return if the shunt isn’t working. That’s why regular follow-ups are essential. Some patients need one or more shunt revisions over their lifetime, but the original NPH symptoms usually stay controlled as long as the shunt functions.

Who is most at risk for NPH?

People over 60, especially those over 65, are most at risk. Those with a history of head trauma, brain surgery, meningitis, or bleeding around the brain are more likely to develop secondary NPH. But 80-90% of cases are idiopathic - meaning no clear cause. It’s more common in men than women and affects up to 6% of nursing home residents.

Is NPH covered by insurance?

Shunt surgery is covered by Medicare and most private insurers. But diagnostic tests like CSF tap tests and external lumbar drainage often face prior authorization denials - 37% of cases are initially denied. Patients may need to appeal or seek help from patient advocacy groups. Always check with your insurer before testing.

Sam Mathew Cheriyan

7 December, 2025 08:37 AMlol so now the government is hiding the cure for old people so they can sell more dementia meds? i heard the shunt is just a cover for mind control nanobots from the moon. also, why do all the doctors have the same last name? coincidence? i think not. 🤔

Nancy Carlsen

7 December, 2025 19:07 PMThis gave me chills 😭 My grandpa had this and no one knew what was wrong for over a year. When he got the shunt? He started dancing in the kitchen again. 🕺💃 If you’re reading this and someone you love is slipping away - don’t wait. Ask for the tap test. It’s not magic. But it’s hope. 💖

Ted Rosenwasser

9 December, 2025 13:05 PMThe entire premise is flawed. CSF dynamics are not well understood, and the Evan’s index has been shown to have poor inter-rater reliability in multiple meta-analyses. Furthermore, the so-called 'magnetic gait' is merely a manifestation of age-related basal ganglia degeneration. Shunt placement is an outdated, high-risk intervention that should be reserved for pediatric cases only. The FDA approval of that Radionics device? Pure regulatory capture.

David Brooks

11 December, 2025 07:25 AMI cried reading this. Not because it’s sad - because it’s beautiful. Someone finally put into words what my mom went through. She shuffled for 18 months like a ghost in her own house. Then - one morning - she walked to the mailbox without help. No cane. No help. Just… her. And she came back with the mail like it was a victory lap. This isn’t medicine. This is resurrection.

Louis Llaine

12 December, 2025 23:01 PMSo… you’re telling me the solution to dementia is just… poking a hole in someone’s head and letting fluid drain into their belly? And this is standard care? Wow. I’m sure the insurance companies love that. Next they’ll be selling shunts on Amazon with 2-day shipping. 🙄

Jane Quitain

14 December, 2025 18:24 PMOMG I just told my dad to ask his doctor about this!! He’s been saying his feet feel stuck and he keeps forgetting his keys… I was like ‘maybe it’s just stress’ but now I’m like WAIT A MINUTE 🙌 You’re right - it’s NOT just aging. I’m printing this out and handing it to him. We got this!! 💪

Ernie Blevins

16 December, 2025 18:20 PMThis is just a scam. Old people get weird symptoms. They get scared. Doctors see a chance to make money. So they stick a tube in them. Then they bill Medicare for $80k. The real problem? Nobody wants to admit their grandma is just… old. So they invent diseases to make themselves feel better. Shunt = profit. Truth = boring.

Helen Maples

18 December, 2025 04:28 AMIf your doctor dismisses this, go to a movement disorder specialist. Immediately. Do not accept 'it's just aging.' You have a right to be heard. If they won't order the tap test, ask for a referral to a hydrocephalus center. There are 12 in the U.S. that specialize in this. I’ve compiled the list - DM me. You’re not alone.

Jennifer Anderson

18 December, 2025 18:32 PMmy aunt had this and no one believed her until she fell and broke her hip. then they finally did the mri. by then she’d lost 2 years. but the shunt? it brought her back. she started gardening again. she remembered my name. i just wish someone had listened sooner. pls don’t wait like we did. 💔

Oliver Damon

19 December, 2025 00:57 AMThe ontological paradox here is fascinating: if CSF accumulation is a compensatory mechanism for impaired glymphatic clearance - which is itself a consequence of aging-related arterial stiffening - then shunting may be merely a symptomatic palliation, not a corrective intervention. The real question isn’t whether the shunt works, but whether we’re treating the symptom while ignoring the systemic neurovascular pathology underlying both NPH and Alzheimer’s comorbidity. The 25–30% overlap isn’t coincidence - it’s convergence.

Ryan Sullivan

20 December, 2025 15:01 PMThe notion that this condition is 'treatable' is a dangerous oversimplification. Shunt dependency is lifelong. Complication rates are unacceptable. And the diagnostic criteria are so nebulous that even experienced neurologists misapply them. The real tragedy isn’t misdiagnosis - it’s the medical industry’s commodification of geriatric decline. We’ve turned a neurodegenerative spectrum disorder into a surgical product. And patients are the collateral.