Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) isn’t a cure for Parkinson’s disease-but for many people, it’s the difference between being stuck in their home and walking the dog again. It doesn’t stop the disease from progressing. It doesn’t reverse memory loss or fix speech problems that don’t respond to levodopa. But when it works, it takes the worst of the motor symptoms-tremors, stiffness, freezing, and uncontrollable movements-and turns them down to a manageable hum.

What Exactly Is Deep Brain Stimulation?

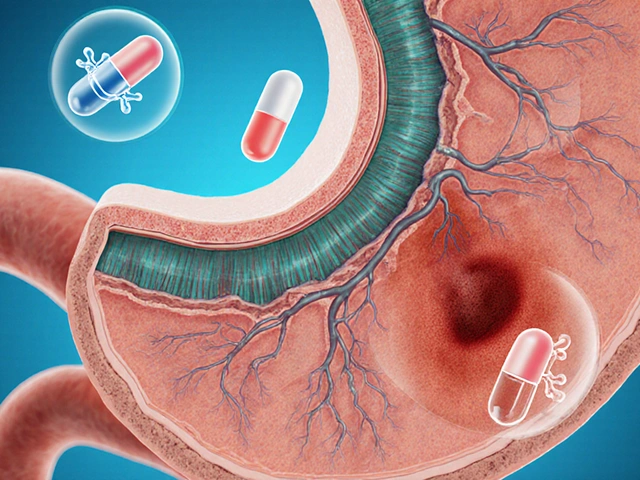

DBS is a surgical treatment where thin wires, called electrodes, are placed deep inside the brain. These wires connect to a small battery pack, usually implanted under the skin near the collarbone or abdomen. The device sends regular electrical pulses to specific brain areas that control movement. It’s like a pacemaker for your brain.

The two most common targets are the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus interna (GPi). STN stimulation often lets patients cut their levodopa dose by 30-50%, which reduces side effects like involuntary jerking. GPi stimulation doesn’t reduce medication as much, but it’s better at smoothing out those jerks and has fewer risks to thinking and mood. Modern systems like Medtronic’s Percept™ PC and Boston Scientific’s Vercise™ Genus™ can even sense brain activity in real time, adjusting stimulation automatically based on what the brain needs.

Each electrode is just 1.27mm wide. The surgery takes 3 to 6 hours. Patients are awake during most of it-because the surgeon needs to test brain responses while placing the leads. A frame holds the head steady. A tiny hole is drilled in the skull. Microelectrodes listen to brain signals. The patient might be asked to move their hand, count backward, or speak. The goal: find the exact spot where stimulation gives the best movement control with the fewest side effects.

Who Is a Good Candidate for DBS?

Not everyone with Parkinson’s is a candidate. In fact, most aren’t. Only about 1-5% of people who could benefit ever get the procedure. Why? Because the bar is high-and it should be.

First, you need a clear diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. DBS doesn’t work for atypical parkinsonism like progressive supranuclear palsy or multiple system atrophy. Those conditions don’t respond to levodopa, and neither will they respond to DBS.

Second, you must have a strong, consistent response to levodopa. If your tremors or stiffness improve dramatically after taking your medication, that’s a good sign. The standard test is a 30% or better improvement on the UPDRS-III motor scale after taking your usual levodopa dose. If you barely notice a difference when you take your pills, DBS won’t help much.

Third, you need to have been living with Parkinson’s for at least five years. This isn’t arbitrary. Early-stage patients often still respond well to medication alone. DBS is meant for when meds start to fail-when you’re having “off” periods where you’re stiff and slow, even after taking your pills, or when you’re uncontrollably twitching during “on” periods. These are called motor fluctuations and dyskinesias.

Fourth, your thinking and mood need to be stable. If you have dementia, major depression, or untreated anxiety, DBS can make things worse. Most centers require a MMSE score above 24 or a MoCA score above 21. Neuropsychological testing takes hours-assessing memory, attention, problem-solving, and emotional state. If you’re struggling to plan your day or remember names, DBS might not be right.

And finally, you need support. DBS isn’t a one-time fix. You’ll need regular programming visits for 6 to 12 months after surgery. You’ll need someone to drive you, help you track symptoms, and recognize when something’s wrong-like an infection at the incision site or a lead shifting position.

What Can You Actually Expect?

Realistic expectations are everything. Too many patients think DBS will stop their disease. It won’t. It won’t fix balance problems, speech issues, or swallowing difficulties that don’t improve with levodopa. It won’t help with constipation, sleep problems, or depression unless those symptoms are tied to motor fluctuations.

But for the right person, the results are life-changing:

- Up to 80% reduction in dyskinesias (involuntary movements)

- 60-80% less “off” time-meaning more hours of good movement each day

- 30-50% lower daily levodopa dose, which means fewer nausea episodes and less “on-off” rollercoaster

- 23-point improvement in quality of life scores (PDQ-39) compared to 12.5 with meds alone (EARLYSTIM trial)

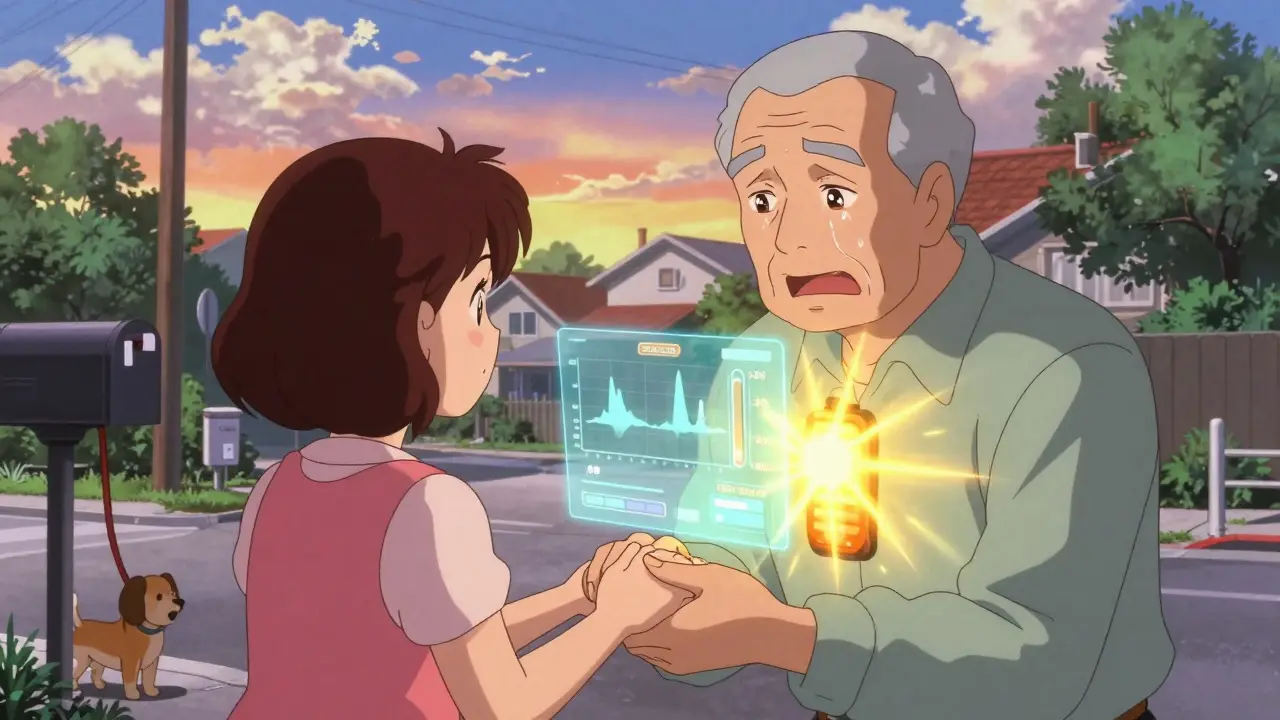

One man in Florida, who had been bedridden for 4 hours a day before surgery, started walking to the mailbox again. A woman in Minnesota stopped dropping her coffee cup. Another patient, who hadn’t hugged his daughter in years because of shaking, held her hand for the first time in a decade.

But it’s not all perfect. About 10-15% of patients need a second surgery to fix hardware problems-loose wires, infections, or battery failures. Some report new trouble with word-finding, slowed thinking, or mood changes. One Reddit user said, “My tremors are gone, but planning a meal takes three times longer.” That’s not rare. The brain areas targeted by DBS aren’t just for movement-they’re connected to decision-making and language.

DBS vs. Other Treatments

What’s the alternative if you’re not a DBS candidate?

Levodopa is still the gold standard for early-stage Parkinson’s. But after 5-10 years, its effects become unpredictable. That’s when DBS steps in.

Focused ultrasound (like Exablate Neuro) is non-invasive and FDA-approved for tremor-dominant Parkinson’s. But it only treats one side of the body, and it’s irreversible. If the results aren’t perfect, you can’t adjust it.

Lesioning surgeries (like pallidotomy or thalamotomy) destroy a small part of the brain to stop symptoms. They work-but they’re permanent. If you get too much stimulation, you can’t turn it off. DBS is adjustable. You can change the settings. You can turn it off. You can replace the battery.

And then there’s the cost. In the U.S., DBS runs $50,000-$100,000. Medicare and most insurers cover it if you meet criteria. But in places without good insurance, it’s out of reach. Even with coverage, you’ll need years of follow-ups, which aren’t always covered equally.

The Bigger Picture: Why So Few Get It?

There are an estimated 10 million people with Parkinson’s worldwide. About 200,000 have had DBS. That’s less than 2%. Why?

Many neurologists don’t refer patients early enough. They wait until the patient is severely disabled. But the EARLYSTIM trial showed that patients who got DBS earlier-after just 4 years of symptoms-had better long-term outcomes than those who waited.

There’s also a lack of specialized centers. DBS requires a team: a movement disorder neurologist, a neurosurgeon trained in stereotactic surgery, a neuropsychologist, and a DBS programmer. Most community hospitals don’t have this. Only centers doing over 50 procedures a year have consistently better results.

And then there’s fear. Patients hear “brain surgery” and think stroke, coma, death. The risk of serious bleeding is only 1-3%. Infection is 5-10%. Most complications are fixable. The real danger? Waiting too long.

What Happens After Surgery?

Surgery isn’t the end-it’s the beginning of a new phase.

For the first few weeks, you’re healing. The device is off. Then, about 4-6 weeks later, the programming starts. This is where patience is critical. The first setting might make your hand twitch. The next might make you feel dizzy. It takes months to fine-tune. You’ll need to keep a symptom diary: “When I took my pill at 8 a.m., I was good until noon. After stimulation turned on at 1 p.m., I felt stiff again.” That data helps the programmer adjust voltage, frequency, and which contacts on the lead to use.

Modern devices with sensing technology can record brain waves. If your brain shows too much beta activity (13-35 Hz), it’s a sign your Parkinson’s symptoms are flaring. The device can respond by increasing stimulation automatically. This “closed-loop” DBS, like Medtronic’s Percept™ PC, is changing the game.

Batteries last 3-5 years if they’re not rechargeable. Rechargeable ones last 9-15 years. But you still need to replace the generator eventually. That’s another surgery-usually outpatient, under local anesthesia.

What’s Next for DBS?

The future is personalization.

Researchers are looking at genetic markers. People with the LRRK2 mutation respond better to DBS. Others with certain brain patterns might benefit more from GPi than STN. One 2023 study in Lancet Neurology showed these biomarkers could predict outcomes better than symptoms alone.

There’s also work on using DBS for non-motor symptoms-depression, anxiety, even obsessive thoughts. Early trials are promising, but it’s still experimental.

And then there’s digital integration. Imagine your Apple Watch detecting tremor spikes and sending data to your DBS device, which then adjusts automatically. Or your phone app reminding you to take your pill and syncing with your stimulator settings.

One thing’s clear: DBS is no longer a last resort. It’s a powerful tool for the right person at the right time. The challenge isn’t the technology. It’s getting the right people to the right place before it’s too late.

Is DBS a cure for Parkinson’s disease?

No, DBS is not a cure. It does not stop Parkinson’s from progressing. It treats symptoms that respond to levodopa-mainly tremors, stiffness, slowness, and dyskinesias. It does not help with balance problems, speech issues, or cognitive decline unless those are linked to motor fluctuations.

How long does it take to see results after DBS surgery?

You won’t feel the full effect right away. The device is usually turned on 4-6 weeks after surgery. Programming begins then and can take 6 to 12 months to fine-tune. Most patients notice major improvements in motor symptoms within the first 3 months, but optimal settings often take longer.

Can DBS help with speech or balance problems?

Usually not. Speech and balance problems in Parkinson’s often don’t respond to levodopa, and DBS doesn’t fix those either. In fact, some patients report worsening speech after DBS, especially with STN stimulation. Balance issues improve only 20-30% at best. If these are your main concerns, DBS may not be the best option.

What are the biggest risks of DBS surgery?

The most serious risk is brain bleeding, which happens in 1-3% of cases and can cause stroke-like symptoms. Infection at the implant site occurs in 5-10% of patients. Hardware problems-like broken wires or misplaced leads-happen in 5-15%. Most can be fixed with another surgery. Cognitive changes, like trouble with memory or word-finding, are also possible but often mild and improve with time or programming adjustments.

How do I know if I’m a candidate for DBS?

You’re likely a candidate if you have idiopathic Parkinson’s, have had symptoms for at least 5 years, respond well to levodopa (30%+ improvement on motor tests), don’t have dementia or severe depression, and are in good general health. A movement disorder specialist will refer you for neuropsychological testing, a 3T MRI, and a team evaluation before approval.

Does insurance cover DBS?

Yes, Medicare and most private insurers in the U.S. cover DBS for Parkinson’s disease if you meet FDA-approved criteria. Coverage typically requires documentation of at least 3-6 months of optimized medication use and proof of motor complications. Pre-authorization is required and can take several months.

How often do I need to see the doctor after DBS?

In the first year, you’ll need monthly visits for programming adjustments. After that, visits usually drop to every 3-6 months. Some patients with newer devices can do remote programming via Bluetooth, reducing the need for in-person trips. But regular check-ins are still essential to monitor battery life, check for complications, and adjust settings as your disease changes.

Can DBS be reversed if I don’t like the results?

Yes. The device can be turned off at any time. The electrodes can be removed surgically if needed, though this is rare. Most side effects improve with programming adjustments. If you’re unhappy, don’t assume it’s permanent. Talk to your team-they can often make changes that restore comfort.

Arjun Seth

15 January, 2026 21:27 PMDBS? Please. I've seen too many people get this done and end up worse off. You think you're getting your life back, but then you can't remember your kid's name or say the word 'coffee' without stuttering for five minutes. It's not magic-it's a gamble with your brain.

Mike Berrange

16 January, 2026 20:01 PMThe article says DBS doesn't fix speech or balance, yet it promotes the procedure as life-changing. That's not honest-it's marketing. If you're going to implant electrodes in someone's brain, you owe them the full truth, not cherry-picked stats.

Dan Mack

18 January, 2026 01:55 AMThey're using DBS to control your brain so they can monitor your thoughts next. The FDA, Medtronic, and Big Pharma are in bed together. They don't care if you live or die-they care about the data stream from your Percept™ chip. That's why they push 'closed-loop' tech. You're not a patient-you're a product.

Amy Vickberg

19 January, 2026 11:37 AMI have a friend who got DBS after 8 years of Parkinson’s. She couldn’t walk to the kitchen before. Now she dances with her grandkids. It’s not perfect, but it gave her back dignity. That’s worth more than any risk.

Nicholas Urmaza

21 January, 2026 03:37 AMIt is critical to understand that deep brain stimulation is not a cure but rather a sophisticated intervention designed to modulate neural circuitry. The clinical evidence supporting its efficacy in reducing motor fluctuations is robust and well documented in peer-reviewed literature. Patients must be evaluated through multidisciplinary teams to ensure optimal outcomes. Failure to adhere to established protocols results in suboptimal results and increased complication rates.

Jami Reynolds

22 January, 2026 23:06 PMDid you know the electrodes in DBS devices can be hacked? There are patents filed for remote access. Imagine someone turning your tremors back on just to mess with you. The government knows this. They don’t tell you because they’re already using this tech for surveillance. Your brain is a network now. And they own the router.

RUTH DE OLIVEIRA ALVES

24 January, 2026 05:06 AMAs a caregiver for a patient with Parkinson’s in a low-resource setting, I have witnessed the profound disparities in access to DBS. While this technology offers transformative potential, its exclusivity due to cost and infrastructure limitations perpetuates inequity. We must advocate for global health initiatives that bring such interventions to underserved communities-not just those with insurance or privilege.

Crystel Ann

26 January, 2026 03:46 AMMy dad had DBS. He still forgets where he put his keys. But he can hold my hand again. That’s all I needed.

Nat Young

27 January, 2026 05:43 AMEveryone says DBS is life-changing but nobody talks about the 30% who get worse cognition or emotional blunting. The studies cherry-pick the winners. The people who regret it? They disappear. You think this is medicine? It’s a numbers game. They need the success rate to look good for investors. Your brain is just a variable in their regression model.

Niki Van den Bossche

27 January, 2026 06:11 AMDBS isn’t just a medical procedure-it’s a metaphysical negotiation. You’re trading your autonomy for motor control, surrendering the chaotic symphony of your neural architecture to a silicon conductor. The tremors vanish, yes-but so does the raw, unfiltered essence of being human. What is a life without its tremors, if not a life without its truth? The soul doesn’t tremble-it sings. And now, we’ve silenced the song to make the body behave.